The ‘Everlasting Fighting’ between Elephants and Dragons

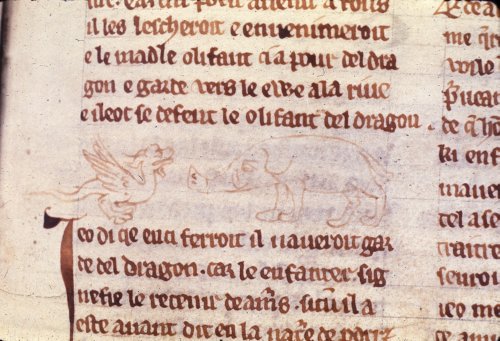

A quick look at medieval illustrations of elephants reveals that they are often depicted in combat with dragons. The serpent is shown having wrapped its long body around the larger animal, as if in some strange embrace. Why was this so popular?

The idea that elephants and dragons are mortal enemies seems to date back at least to the early Middle Ages, and was influenced by ideas from the Bible. The Medieval Bestiary notes that “the elephant and its mate represent Adam and Eve. When they were still without sin in the Garden of Eden, they did not mate, but when the dragon seduced them and Eve ate the fruit of the tree and gave some to Adam, they were forced to leave Paradise and enter the world, which was like a turbulent lake of pleasures and passions.”

Medieval writers often mention the animosity between the two beasts. One of the most interesting comes from Bartholomaeus Anglicus, a 13th century Franciscan monk who lived in England, and wrote a wide-ranging work on nature entitled De proprietatibus rerum. Here is his section on dragons:

The Dragon is most greatest of all serpents, and often he is drawn out of his den, and rises up into the air, and the air is moved by him, and also the sea swells against his venom, and he has a crest with a little mouth, and draws breath at small pipes and straight, and rears his tongue, and has teeth like a saw, and has strength, and not only in teeth, but also in his tail, and attacks both with biting and with stinging, and has not so much venom as other serpents: for the dragon to slay anything, his venom is not needed, for whom he finds he slays, and the elephant is not secure of him, even with all his greatness of body. Often four or five of them fasten their tails together, and rear up their heads, and sail over seas and over rivers to get good meat.

Between elephants and dragons is everlasting fighting, for the dragon with his tail binds and spans the elephant, and the elephant with his foot and with his nose throws down the dragon, and the dragon binds and spans the elephant’s legs, and makes him fall, but the dragon takes it full sore: for while he slays the elephant, the elephant falls upon him and slays him too. Also the elephant seeing the dragon upon a tree, goes him to break the tree to smite the dragon, and the dragon leaps upon the elephant, to bite him between the nostrils, and attacks the elephant’s eyes, and sometimes blind him, and sometimes leaps upon him from behind, and bites him and sucks his blood. And at last after long fighting the elephant becomes feeble for great blindness, in so much that he falls upon the dragon, and slays in his dying the dragon that killed him.

The cause why the dragon desires his blood, is coldness of the elephant’s blood, by the which the dragon desires to cool himself. Jerome says, that the dragon is a full thirsty beast, insomuch that he may have water enough to quench his great thirst; and opens his mouth against the wind, to quench the burning of his thirst in this way. Therefore when he sees ships sail in the sea in great wind, he flies against the sail to take their cold wind, and sometimes overthrows the ship because of the greatness of its body, and the strong force against the sail. And when the sailors see the dragon coming, and know his coming by the water that swells against him, they strike the sail at once, and escape in this way.

You can read a full translation of Bartholomaeus’s work in Medieval lore : an epitome of the science, geography, animal and plant folk-lore and myth of the middle age, which is available via Archive.org.