Introduction to a New Model

The new infantry model

At about the same time that I first developed The Roman Army web page Adrain Goldsworthy's book, The Roman Army At War was published. It was followed by articles by Dr. Philip Sabin: 'The Mechanics of Battle in the Second Punic War and The Face of Roman Battle'; and by Alexander Zhmodikov: 'Roman Republican Heavy Infantrymen in Battle'. Together these authors, though they do not agree on all points, have developed ideas that lead to a new way of thinking about how the Romans actually fought. This update is an effort to create visual models that reflect some of those ideas. The models are my own interpretation of their thinking. They represent an effort to come to a general synthesis and so focus more on elements they have in common than on points in which they differ. My interpretation does not faithfully present the ideas of any of these authors but is my own personal interpretation of their thinking. In fact, Dr. Sabin and Zhmodikov disagree with portions of my models, as will be noted later.

I am also indebted to Ed Valerio and Steven James who have shared their vast knowledge of Roman warfare with me. They have provided a great deal of supplemental information, have contributed many ideas that fleshed out the material and have offered helpful criticism of nearly every sentence. I would also like to thank the many other people who have written and continue to write with information, ideas, and suggestions. This interaction helps ensure that this page is truly a work in progress, not a static artifact.

"A Model" not "The Model"

The goal here is to offer a way of visualizing what Roman fighting might have been like. There can be no definitive single model. The Roman army changed over time and from place to place. Its tactics depended on the circumstances, the general, the enemy, and, for all we know, on the omens. The purpose of these images is not to say this is how it was done but merely to offer one way of visualizing how the Romans may have fought. Hopefully, the models will raise yet more questions, identify problems with standard descriptions, and provide some new insights.

Zhmodikov distinguishes between two types of battles: defensive and offensive. He points out that the tactics of each were quite different. The model being explored here is offensive, an exploration of a defensive model would have to await another time.

How the Roman soldier fought

Goldsworthy, following Keegan in his The Face of Battle, focused attention on the importance of understanding the experience of the individual soldier if we are to grasp what ancient war was. Grand maneuvers aside, what actually decided the nature of battle was the experience of the individual. These first sections will present several aspects of the individual experience of combat that affect the overall model of fighting.

Keegan: (p.303) "The study of battle is therefore always a study of fear and usually of courage; always of leadership, usually of obedience; always of compulsion, sometimes of insubordination; always of anxiety, sometimes of elation or catharsis; always of uncertainty and doubt, misinformation and misapprehension, usually also of faith and sometimes of vision; always of violence, sometimes also of cruelty, self-sacrifice, compassion; above all, it is always a study of solidarity and usually also of disintegration - for it is toward the disintegration of human groups that battle is directed."

Fear

Goldsworthy: (p.257) The century seems to have been the most important subdivision of the legion. It was the one with which the soldiers themselves most closely identified, and used to describe themselves on inscriptions. … Even more intimate than this was the contubernium of eight men. These men lived and ate together in a small tent on campaign … Modern studies have suggested that the bond between such small groups of soldiers is so great that, more than anything else, the desire not to lose face in the eyes of this small group and the fear of not showing as much endurance in the face of danger as his comrades, helps a soldier to cope with the stress of battle and prevents him from running away."

Some books discuss the Roman soldier in terms of training and discipline. They present him as almost an automaton who advanced fearlessly into battle, confident in his arms and tactics, rigidly following his officer's orders. In fact, this was not the case. When faced with the prospect of imminent death or dismemberment, every soldier feels fear and there are numerous examples in Caesar's own writings that show that fear and even panic were common emotions.

To fear, add a high level of discomfort. Keegan offers a compelling description of soldiers standing in formation awaiting the battle of Agincourt: hungry and thirsty; wired up with nervous energy; tired from the exertion of daily marches and lack of sleep; urinating and defecating in place because they could not leave the ranks. His descriptions, though of a later time, must surely be applicable to Roman battles as well. We know that battles were often fought in hot, windy, dusty conditions; that they were often preceded by strenuous labor on the part of one army or the other; and that the two armies might stand in place for hours before one side launched an attack.

When the experience of the individual soldier becomes the focal point then there are a number of implications for how the actual fighting might be imagined.

Fear apparently makes all men in all armies want to bunch up for mutual protection. In ancient armies, this was observed in the gradual angling of the battle line as the army moved forward. Each soldier consciously or unconsciously sought shelter behind his neighbor's shield on his right. As each man incrementally moved closer to and slightly behind the man on his right it caused the entire battle line to become advanced on the right side. This seems to have true of all ancient armies that fought in an organized formation.

Fear makes the use of weapons less efficient. There are examples, even in modern war with guns against tight formations of men and at close range where only 25% of shots fired hit anything at all. Since it was virtually impossible to miss at that range, the conclusion is that most of the men either never fired a shot or, if they did, they fired at nothing. The theoretical effectiveness of arrows, darts, the pilum, or even the scutum and gladius would be significantly reduced.

It is said that most men in battle seek to save their own lives, not to kill the enemy. This is probably hard to quantify but the numbers used are that 75% fight to not get hurt and only 25% fight to hurt the enemy. The 75% do not fight aggressively or efficiently. In the context of Roman fighting, their swordplay would be tentative, their thrusts ineffective. They may not even actually engage the enemy but may stay just inches out of the reach of the weapons. The remaining 25% do fight aggressively and it is this group that leads the attack, opens gaps, exploits opportunities, rouses the laggards, rallies the tired troops for yet another "go."

As an aside, this is one area in which the limitations of the experiences of reenactors and SCA fighters are most obvious. These fighters engage in the contests out of a sense of fun and excitement. There are no consequences to their battles. The participants are eager to engage in fighting. Quite different from the real thing. If SCA fighters were obliged to put up a large amount of money, say $30,000, which they would lose it if they were "wounded" then, perhaps, their fighting style might begin to resemble real combat.

If the 25% who were aggressive fighters were distributed randomly throughout the body of men then only 1 in 16 encounters would bring two aggressive men opposite each other in the fight, 6 encounters would bring one aggressive man against a non-aggressive man and probably result in the non-aggressive man being pushed back or wounded, and the remaining 9 encounters would be between non-aggressive men.

However, it may be unlikely that the distribution was random. One might assume that the centurions would be among the more aggressive individuals. The high casualty rate for this group is evidence of something like that. Furthermore, a good centurion, given the opportunity, would almost certainly put his best, most aggressive, fighters in the front rank. So, in actual fact, it may well have been that the entire front rank was comprised of aggressive fighters.

What this might have meant, though, is that attacks by the other ranks would be far less effective since they would be composed almost entirely of non-aggressive fighters.

Goldsworthy felt that Roman tactics may have been as directed toward keeping men from running away from battle as toward winning it outright. For example, the depth of the formation and placing the optio at the rear of the formation would serve to keep stragglers in line and prevent the less brave from turning back. Similarly, the fortifications of the camp would serve to keep soldiers in as well as the enemy out.

Any good representation of Roman fighting would need to be aware of these factors.

Confusion

One can only try to imagine the confusion inherent in an ancient battle.

It would have been difficult for anyone to see much of what was happening. A small army, the equivalent of just four legions plus cavalry, would have a front of nearly a mile. A larger army, typical of the late Republic and early Empire, might be made up of 8 to 12 Legions and have a front of several miles. Moreover, battlefields were selected because they were flat and allowed the armies room to maneuver. But, being flat, they offered no vantage points higher than the back of a horse. Because most warfare took place in the summer months, dust would have been a frequent problem. Distance and dust would have made it nearly impossible to tell what was happening at other parts of the battle.

The noise would have been horrific. Initially, there would be the sounds of trumpets and thousands of men yelling on both sides. During the battle there would be added the sounds of shields and swords smashing together, orders shouted, men calling encouragement to their comrades or shouting threats to the enemy, the thunder of horses hooves, the cries of wounded and dying men. It is possible that the regular infantryman could hardly hear his own officers.

The nice neat unit formations we see on paper simply disappear, replaced by a melee of men. The battle line is not straight, or well defined, or stationery. Rather there is a moving seething mass of men sometimes hotly engaged, sometimes falling back. At a quick glance, it would be difficult to tell which side was having the better of it. At times it was, apparently, even difficult to tell which side was which. As an example of just how confusing battle could be Goldsworthy cites the incident of Galba actually crossing over into enemy lines without even being aware of it.

Modern SCA fighters note that even in their small scale friendly warfare it is impossible to know what's happening a mere 20 or 30 feet away. Roel van Leeuwen says: "It is very difficult to really understand whether you are winning or not." Robert Sulentic says: "My own experience as a reenactor tends to make me think that (1) one is usually way too busy watching what is going on to your front to even notice what is going on behind you, and (2) lines of men tend to naturally 'spread out' as individual soldiers find a comfortable space in which to work, so to speak." Robert's comments show both the strength and weaknesses of the testimony of reenactors and SCA combatants. In his first remark, he notes that the fighter is focused on the enemy opposite him to the exclusion of everything else. If this is true in mock combat where the price of defeat is, at most, a bruise to the ego, it must be all the more true where the price is a painful death or dismemberment. The second comment shows, I believe, a critical difference. In mock combat, the participants engage for their own amusement. Put simply, they want to fight because they find it fun. Quite different from the real thing in which individuals do not want to be wounded or killed. Recreational fighters might spread out so that they can "get in on the action" whereas real soldiers tend to bunch up for protection from the action.

Any model of Roman fighting has to depart from the tidy paper diagram and reflect the inherent confusion of the real place. Elaborate maneuvers and complicated tactics would probably not have even been possible. It would have been important for the individual soldier to stay in close contact with his comrades on all sides of him, to feel and sense their presence and support even when he was tightly focused on the enemy in front of him. Any sort of coordination between units must have been difficult and, at times, impossible. Large scale coordination would have been extraordinarily difficult, but not impossible as we will note later.

Command and control

The ability of the commander to control his army during battle was probably not great.

As noted above, it would have been difficult to see or hear much of what was happening during the battle.

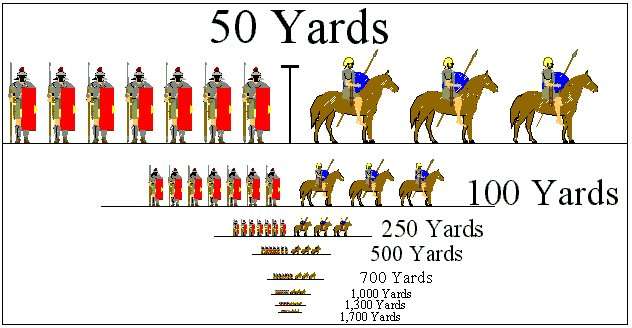

Goldsworthy gives a chart of what can be seen at various distances on page 152 of his book.

Figures given in the Victorian Artillerists' Manual on recognition distances provide us with a useful guide [to what can be seen on the battlefield]:

1,700 yards - masses of troops can be recognized

1,300 yards - infantry can be distinguished from cavalry.

1,000 yards - individuals can be seen.

700 yards - heads, crossbelts etc. can be distinguished

500 yards - uniforms recognized, reflections from weapons

250 yards - officers recognizable, uniforms clear

The following drawings accurately illustrate what detail can be seen at various distances.

For an approximately accurate perspective view hold a ruler at arm's length and position yourself so that the black T under the words "50 Yards" looks like it is 1 inch high. At 1,700 yards very little could be seen. Large Roman armies, such as those used during the civil wars, could number 10 or more legions. Such an army would have a front of around 3,000 yards, twice the distance shown in the chart above. At that distance men and horses would be mere specks.

Visibility would be obstructed by men and horses in the line of sight. The ability to distinguish friend from foe would be more difficult when seeing units from the sides or back. Everything would be in motion. And even a little dust in the air would significantly reduce the amount of detail and color that could be seen at a distance.

Roman commanders seem to have favored a position on their right flank, traditionally the strongest and most aggressive wing of the army. Even Pompey at Pharsalus, where the major action was expected on the open left flank, took up his position on the right. From this side, a general could hardly have seen what was going on some 1,700 yards away on the left flank. For information, he would have had to depend on messengers or other indicators. Pompey is said to have deduced the outcome of the cavalry fighting by observing the dust clouds raised.

Overall, the commander's ability to see what was happening was severely limited. He would have had to depend upon dispatch riders for information. Goldsworthy (p. 152), provides some data: "A 1914 Military Manual gave the speed of dispatch riders as 'ordinary - 5 mph; rapid - 7 to 8 mph; urgent - 10 - 12 mph'." Considering the difficulty of getting around it during an actual battle the messenger would be doing well to average more than the "rapid" pace described above.

If the riders could travel at the "rapid" pace of 8 mph it would take about 13 minutes to ride the length of a 3,000-yard battlefield. By the time the general could receive the report, issue new orders, and send the rider back there would be a delay of nearly 1/2 hour. Some battles may have lasted half-a-day, but others were over in a matter of a few hours. In those cases, a delay in communications of 1/2 hour would be significant.

For this reason, the Romans used horns to signal orders over long distances. The general would still be dependent on dispatch riders to give him information about the status of events at distant points but he would have been able to issue simple types of commands via horn signals. Keeping noise factors in mind, there would have had to have been a relay system to ensure communications with the furthest units.

The conclusion is that the general could become aware of situations at the further end of the battlefield in about 10 to 15 minutes. He could issue commands to execute simple pre-formed tactics via the standard set of horn signals. If he wished to order a legion to perform some special maneuver it would have had to have been done by dispatch riders and could have taken another 10 to 15 minutes to relay. It was probably impossible to execute any complicated set of tactics that involved extensive coordination. Tactics had to be relatively simple and the general's ability to change the battle plan was quite possibly limited to pre-set signals sent by horns or to an oral instruction delivered by a dispatch rider.

All of this being said, it is quite clear that the Romans did have a fair degree of tactical control over remote units on the battlefield. There are numerous instances in Caesar's De Bello Gallico and De Bello Civili of both cohorts and whole legions being ordered to perform maneuvers during the course of a battle. There are no descriptions of units smaller than the cohort ( e.g., a century) taking any independent action. The implication is that legions and cohorts operated somewhat independently, under the direction of the wing commander or the legion tribunes, the primus pilus, or even at the command of the local centurions. The commanding officer could not effectively manage the affairs of the entire army. Therefore, battlefield tactics that involve highly complicated maneuvers that originated from a single command center could probably not have been effective.

Goldsworthy comments along these lines, pointing out that most Roman battles were straight forward affairs, a mighty clash of two armies charging more or less straight ahead at each other. Occasionally a flanking maneuver or even ambush might be tried, but these were the exceptions.

Simple tactics

Tactics and maneuvers had to be simple for other reasons.

Stress

Under the extreme stress of combat adrenaline, fear, and confusion limit people's ability to function well. Even in a simple modern sporting event we can see highly trained professional athletes forget the most basic things like where they are on the ball field or how much time is left in the game. We should not expect that any individuals in combat would or even could remember a complicated set of drills.

There is evidence that, in battle, there is a tight focus. The individual sees only the perceived threat immediately in front of him. And naturally so. His whole instinct is simply to stay alive, to avoid the killing stroke the other fellow is aiming at him. In these situations, the soldier simply will not notice much else.

The implication is that at all levels we should imagine that things were kept simple. The soldier probably could not execute elaborate drill-type movements during battle. All kinds of line replacement schemes depend on intricate drills, ranks, and files moving in a neat, orderly fashion. It probably didn't happen. And, at the larger scale, it would have been difficult for a cohort or legion to execute complicated battlefield maneuvers if the ability of the individual to execute the drills could not be counted upon. Therefore, at all levels, it is likely that tactics were pretty simple.

Battlefield obstructions

Intricate maneuvers would be hampered by an assortment of obstructions on the battlefield. Most depictions ignore this.

True, most battles were fought on relatively flat smooth ground. Even a flat field would have many minor obstructions. A relatively small boulder or bush could seriously disrupt the tidy ranks and files that appear on paper.

In addition to natural obstacles, there would be a considerable amount of debris from fighting. Along a front of 100 men, there would be between 200 and 400 pila that had been thrown - many now stuck in the ground, some (say, a dozen) lodged in a discarded shield or in the corpse of a casualty. Along that same 100-man front, a casualty rate of just 3% would leave six bodies (three from each side) lying on the field. Near each of the six bodies would be a sword or spear, a shield, and possibly a helmet lying on the ground as well. There could be another twelve wounded who may have been removed from the field but whose equipment might be lying around.

A front of 100 would take up roughly 300 feet. Along that front there would be one pilum every nine inches, a pilum-scutum tangle every 25', a body every 50' and equipment of the dead and wounded every three feet. This detritus of battle could be scattered for some distance on either side of the current line of fighting, but even so, it would remain as an obstacle to troop movement. Just about every century on the line would find itself moving over and around these obstacles. At a minimum, this would disrupt the ranks and files. It could be much more serious when soldiers tripped and fell, as they would almost inevitably have done.

Maneuvering by any unit would have to be over and around these obstacles. It is not impossible to maneuver, but it is not as simple, orderly, and precise as it appears on paper.

Training

Also arguing against complicated battle tactics is the fact that many legions were raised hurriedly and placed into combat with little training time. If new legions could be made ready to fight alongside veteran legions in a relatively short period of time then the tactics the army engaged in cannot have been more complicated than those the new legions were capable of executing. Even if new soldiers learned certain maneuvers on the drill field, with only weeks of preparation they could hardly have been expected to execute them in the heat of battle. Therefore, tactics probably had to be kept quite simple, at least in these instances. It is likely that tactics were always pretty simple, a conclusion Goldsworthy would endorse.

The need to keep things simple will influence how Roman fighting is visualized. For example, it makes the elaborate maneuvers necessary for the type of line relief described by Livy seem less and less feasible.

Hand-to-hand fighting was brief and sporadic

There seems to be a general consensus that hand-to-hand fighting was necessarily brief and therefore had to be sporadic. The exertion required for any type of combat is such that even the best-conditioned individual will become exhausted in a matter of minutes. How long would certainly depend on the powers of the individual and the circumstances of the fighting - the type of enemy, aggressiveness of both parties, time of day, temperature. A good estimate is that serious hand-to-hand fighting could not last longer than 15 minutes and probably lasted a lot less. 5 minutes is not an unreasonable average, though Sabin thinks even that may be too long..

If combat only lasted a few minutes then either there had to be ongoing replacement of the front ranks or fighting had to stop. Some older authors tried to describe systems of replacement to bring fresh men to the front almost continuously. Today the consensus (Goldsworthy, Sabin, Zhmodikov) seems to be that the fighting itself was sporadic.

After a few minutes of fighting the two sides backed away from each other by mutual consent and by necessity. There followed a lull in the fighting that could last a few minutes or quite a long while. Most of the time of a battle was spent in these periods of lulls in the fighting and only a very small portion in actual fierce hand to hand combat.

This realization leads to some significant changes in the way that battles can be imagined. There needs to be a process of attack and falling back. There is a lengthy period of non-contact during which the armies may have been throwing things at each other. After the initial clash of arms, subsequent hand-to-hand fighting may have originated on a local basis, perhaps at the level of the century. The way in which the battle line moves back and forth over time is significantly different. Lulls in the fighting may provide a window of opportunity for line relief schemes that are not possible during close contact fighting.

These are some of the ideas that will be explored in the new models.

Few casualties

Casualty statistics for ancient armies are relatively consistent. Gabriel and Metz in their book From Sumer to Rome offer an analysis of casualties. On page 86 they conclude "On average, the percentage of dead suffered by a defeated army was 37.7%. [...] Death rates for victorious armies, however, were considerably lower, about 5.5%. [...] The disparity in kill rates suggests strongly that most of the killing occurred after one side or the other broke formation and could be hunted down and slain with comparative ease." They go on to conclude that the number of wounded was roughly similar to the number killed in each case.

Furthermore, in their study of battles with known casualty figures they included the battles of Pharsalus and Munda which featured two Roman armies fighting each other. In these battles Caesar lost 1.4% and 2% killed respectively while the loser lost 33% and 41.2%.

Low casualty rates reflect on the effectiveness of weapon systems. If casualties could average around 5% and be as low as 2% then none of the weapons used could have been very effective. Visualizations of the charge, for example, need to reflect this low casualty rate.

It will also be important to make some general decisions about how to distribute casualties over time, during the course of the entire battle. Although some battles were decided at the first onrush, others could last half a day. Two hours would not be a bad estimate of an average battle from initial charge to the time that one side or the other broke and ran.

Based on Gabriel and Metz's analysis it would seem that both armies suffered casualties in the vicinity of 5.5% during the time they were fighting face to face. To build a model of fighting the casualties were divided between those caused at the initial charge and those that came during the course of the battle. With no data to base a guess on, the casualties were arbitrarily divided evenly between the two phases; that is, ½ of the casualties occurred during the initial charge and the other ½ were spread out over the duration of the battle more or less evenly. If the initial charge sequence is taken to have lasted roughly 20 minutes then there are 1 hour and 40 minutes of the 2-hour battle remaining. During that 100 minutes 2¼ % of the casualties occur. Casualties occur at a rate of ¼ % every 20 minutes.

The basic casualty rates are pretty sound, the apportionment of casualties to different parts of the battle is quite arbitrary but necessary for the construction of a model. Later it will be seen that the casualty rates have implications for the way Roman fighting can be visualized.

Moving large numbers of men

Actual battlefield tactics must have been conditioned by the task of moving blocks of men on the field in a coordinated way. The standard wisdom is that columns of men move more easily than lines and that it is difficult or impossible to work with large groups.

The Roman century of 80 men seems to be close to the limit of the size of a unit that can be effectively coordinated. The formations used by the legion almost certainly reflect this need to move blocks of men.

In this respect, a comment by a reenactor is interesting. Ron Hauser: "I found it interesting when I was looking at the early Livy legion that the century was 30 people and a maniple was 60. We have had single, undivided units of 100+ people in some battles, but this monolith was un-moveable. Current thinking in our group is that 50 is the absolute biggest single unit that can be maneuvered, and it has to be fairly deep, i.e. 8 files wide and 6 ranks deep. It also is recognized to require a minimum of 2 officers to do it, 3 is better. We arrived at that value empirically, from repeated wars, but it does somewhat correlate with the Livy model. " Again, mock battle experiences cannot be taken as definitive for the real thing, but in some cases, they do provide a modern insight and confirmation.

A complete model of Roman fighting would show troop movement organized by the centuries, not by cohort.

Sources

John Keegan, The Face of Battle. The Viking Press, 1976.

Peter Connolly, Greece and Rome at War, Frontline books 2016

John Warry, Warfare in the Classical World, University of Oklahoma Press, 1980

Hans Delbruck, Warfare in Antiquity, Volume 1, University of Nebraska Press, 1990