The Face of Ancient Greek Battle - the evidence of Greek Tragedy, Comedy and Philosophy

The 1976 book The Face of Battle, by John Keegan, has been immensely influential in the world of military history. Keegan's work (which explored the battles of Agincourt, Waterloo and the Somme) ushered in a raft of publications which explored the practical mechanics of battle and soldiers’ personal battle experience across a whole range of periods and conflicts. Even in the realm of ancient warfare where personal reminiscences of war are extremely rare, Keegan’s work has had influence (such as in Philip Sabin's 'The Face of Roman Battle' JRS 90 (2000), pp. 1-17). We do have some surviving accounts by soldiers who served (such as Xenophon and Ammianus Marcellinus (even by less well known historians like Velleius Paterculus or Eutropius), and, of course, accounts by men who commanded such as Thucydides, Aeneas Tacticus, Julius Caesar, Josephus, Polybius, even Sextus Julius Frontinus. All of these accounts, however, and the others we have which may have been produced by men with no experience of war, do not offer the kind of information on the personal experience of war which such 'face' accounts require although they are often essential for the practical mechanics of ancient military history.

Instead, historians have imagined the ancient battle experience based on what we know (or what we think we know) from the sources. Novels like Steven Pressfield's Gates of Fire (1998) or Tides of War (2000) and many others have attempted the same thing although in the less restrictive world of fiction. Accounts of ancient Greek battle experience which may be informative for a face of ancient Greek battle but which fall outside the realm of historical accounts come from a variety of sources. Some time ago (in Ancient Warfare 7.4), I wrote about the insights we might get about how warfare was fought and perceived from Greek lyric poetry, but there are other sources. The Athenian tragedians and comedians, and the philosophical works of Plato can provide us with further insights. The many speeches which survive from Athens, where the speakers served in the city’s armies, also provide insights – in fact, so many they need a blog of their own. For today’s purposes, however, the plays of Eupolis, Aeschylus, Aristophanes and Euripides provide insights into the battle experiences of individual soldiers, and in some works of Plato we find further insights into life on campaign during Socrates' career.

Aeschylus

Image (right): Bust of Aeschylus now in the Naples National Archaeological Museum

Image (right): Bust of Aeschylus now in the Naples National Archaeological Museum

The Persae of Aeschylus was first produced in 472 BC, eight years after the events it describes. The play tells the story of the battle of Salamis and is the only historical tragedy to survive. Aeschylus himself had served at Salamis and his play seems to record some of this ‘face of battle’ experience despite being set at the Persian court. More famously, Aeschylus fought at the battle of Marathon (this fact, and only this fact, was recorded on his tombstone). His brother Cynagerius also fought, and died, at the battle of Marathon, and he may have been depicted on the Painted Stoa in Athens in commemoration. His younger brother Ameinias commanded a trireme at Salamis, and won the award there for bravest Athenian commander. As a hoplite (as he had been at Marathon), Aeschylus probably served as a marine at Salamis, an epibates on the deck of a trireme (each ship had fourteen such men). The character of the Messenger who reports the outcome of the battle of Salamis (lines 353-432) in the play, provides some of Aeschylus’ eyewitness testimony. He tells us that the marines boarded their ships the night before the battle and the squadrons stayed in formation, riding the waves during the night. At dawn, the Greeks sang the paean and rowed to battle, the right-wing leading the way and the rest of the fleet following. He tells of each captain choosing a target and rowing to ram them, of the Persians resisting at first but then, crowded into a narrow space, they could not manoeuvre and the Persian ships became fouled with one another. The Greek ships, more coordinated, were able to ram the confused enemy at will. Several Persian ships capsized and the wreckage and crews filled the water, the enemy killed as they floundered. Next, Aeschylus tells of the Persians who had been stationed on the island of Psyttaleia (lines 447-471) and of the Greeks who landed there, wading ashore in their bronze armour and pelting the Persians with rocks (thrown by psiloi) and with arrows by the archers (each trireme had at least four). Limbs were hacked off until not a single Persian survived. Several of Aeschylus’ details accord with Herodotus’ account of the battle (8.84-93) (although there are some differences – Herodotus has the Persians attack the Greeks as they were putting to sea), but Aeschylus’ account is filled with details observed first-hand.

Comedy

Comedy

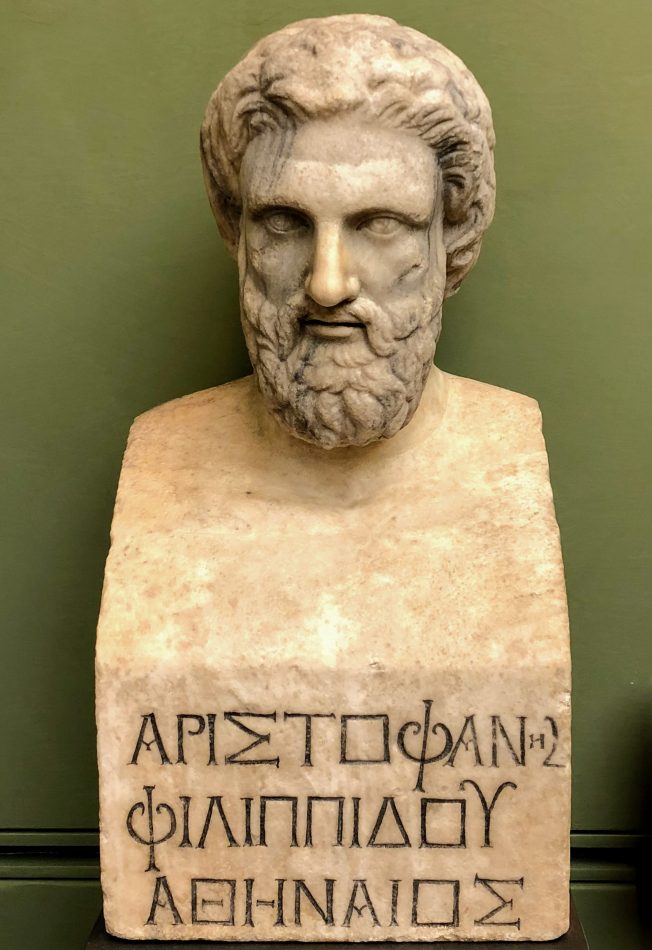

Image (left): Roman copy of a bust of Aristophanes now in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

We saw in an earlier blog post that Euripides’ Suppliants (produced in 423) may have been influenced by the battle of Delium, fought late in 424, and that other playwrights may have used their own experiences in their plays. In Eupolis’ comic plays (which survive only in fragments) we find his experience of being a rower referred to, and his attitudes to who was appointed general at Athens and how they performed (see Ancient Warfare 14.1). In the same vein, Aristophanes’ similar observations are better known and occur across several of his plays (Frogs, Knights, Acharnians, Peace, Lysistrata and Thesmophoriazusai). In Frogs, Aristophanes might even give us insights into the rowing chants of the Athenians (a detail no historian records – lines 208 and 1073) – “O opop, O opop” and “ryppapai” probably called out by the exhorter (keleustes) as the men rowed – these may have provided the rhythm (if not the actual words – although analogies to phrases like ‘yo-ho-heave-ho’ and other seafaring songs may be useful here.

Philosophy and Socrates

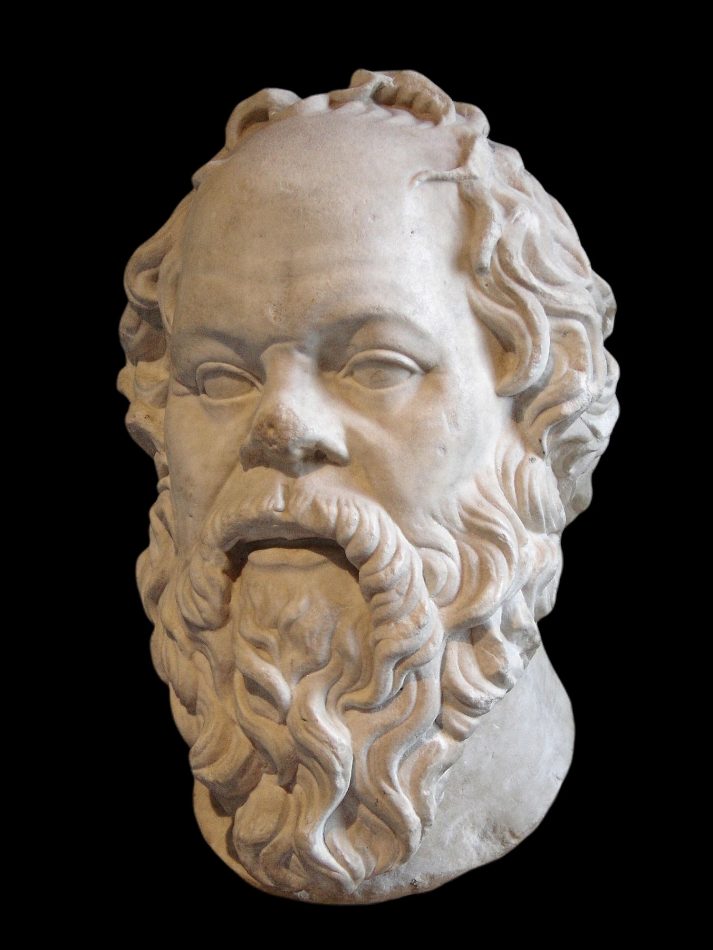

Image (right): Bust of Socrates now in the Louvre, Paris.

Image (right): Bust of Socrates now in the Louvre, Paris.

The military career of Socrates is an aspect of the philosopher’s career which is usually passed over quickly – but one which the dialogues of both Plato and Xenophon record in great (albeit scattered) detail. What is more, those accounts preserve details not usually found in historical accounts. We know Socrates served as a hoplite at Potidaea in 433/2 BC, at Delium (424) and Amphipolis (422) (Potidaea - Plato Apology 28E, Plato Symposium 220D-E, Plutarch Alcibiades 7.2-3), at Delium - Plato Apology 28E, Plato Symposium 220D-221C, Plutarch Alcibiades 7.4, Strabo 9.2.7, Diogenes Laertius 2.22, and at Amphipolis - Plato Apology 28E). Yet Socrates was already thirty-seven in 432 so must have served as a hoplite before that date. There were several occasions during the Peloponnesian War when every available man at Athens was called to serve. It follows that Socrates must have fought on those occasions too.

In several of the dialogues of Plato (and other sources) we find remarkable details of Socrates’ conduct on campaign such as the stories of his endurance (karteria) and his standing all night whilst on campaign at Potidaea (Symposium 219E-220D) or of his saving the life of Alcibiades there (Symposium 220D-E, Plutarch Alcibiades 7.2-3)). He may also have saved the life of Laches at Delium (Symposium 221A). None of our surviving historical accounts of these battles mention Socrates, but his described conduct adds to our understanding of how they were fought and the personal battle experience of an individual hoplite. In fact, Socrates is actually the one hoplite about whose career we know the most. As one example of the insights we can gain from this kind of source, we know that Socrates and Alcibiades were tentmates (synesitoymen – Plato Symposium 219E) at Potidaea. Alcibiades was from the deme of Scambonidae, the tribe of Leontis, whereas Socrates was from the deme of Alopece, in the tribe of Antiochis. This tells us that two men from different tribes could mess together on campaign (and therefore men not in the same file of the hoplite battle line or even from the same deme would share a tent with one another). This tidbit provides fascinating insights for how Athenian camps may have been organised on campaign although we don't know how they moved from these multiple tents to their place in line. What is more, the tribes of Leontis and Antiochis must have been stationed close to one another in the battle (in order for Socrates to save Alcibiades’ life) and this adds further information to where the tribal taxeis stood next to one another in Athenian battle lines. We can note (as we did in an earlier blog) that Leontis and Antiochis had been stationed next to one another at Marathon too (Plutarch Aristides 5). In fact, the best evidence of the ten tribal taxeis and their varying place in line in Athenian armies comes from a speech by Lycurgus – but that is a blog for another day. As ancient military historians, it sometimes pays to think outside the box of what constitutes evidence because you may find it in the most surprising of places.