Archaeology in Israel (2)

In the first part of this article, I explained how information from ancient sources is not always confirmed by archaeology. In asymmetric situations like these, “maximalists” assume that the information from written texts can be accepted: this is supposed to be reliable unless archaeology contradicts it. “Minimalists”, on the other hand, think that information from written sources can only be accepted if it is archaeologically confirmed.

Usually, it is not important which of these two research strategies is preferred. No Englishman cares there is no archaeological confirmation for Caesar’s claim to have invaded Britain and no Iranian is worried that Herodotus’ seven walls of Ecbatana have not been found. This is different in Israel, where there is no unequivocal archaeological evidence for the powerful state of King Solomon. Given the fact that Israel has supporters who believe the Bible to be literally true, and given the fact that it has enemies who will mercilessly point out flaws in the Biblical narrative, the asymmetrical evidence has political consequences.

As it happens, there are several great, stone monuments which were certainly built by a well-organized state. They date, more or less, to the reign of Solomon, who ruled from about 970 to 930 BC. The problem is the “more or less”: archaeologists are not sure when the period to which these monuments belong, “Iron IIa”, started. On the one hand, there is Amihai Mazar, who thinks that Early Iron IIa started early, in about 1000 BC. So, Solomon may have been the builder of the stone structures. Mazar’s colleague Israel Finkelstein, on the other hand, prefers a more recent beginning of Iron IIa: in about 900 BC, during the reign of one of Solomon’s successors.

The two archaeologists are moving towards a compromise. In 2011, Mazar had already agreed that his initial 1000 BC might as well be 970, while Finkelstein sees no objection to 940.

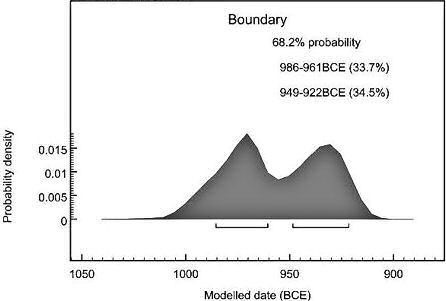

This kind of problem can be solved by testing radiocarbon samples from organic material from early Iron IIa sites. Collect a good number of samples, combine their probability margins, and you end up with a nice curve with a recognizable peak, which indicates the most probable moment for the beginning of Iron IIa. In this particular case, however, the curve turned out to have two peaks, one for the interval 986-961, as Mazar prefers, and one for 949-922, as Finkelstein assumes. No clear solution there then!

Obviously need more radiocarbon samples are needed. To collect these, archaeologists have conducted digs at Megiddo, a site that is exceptionally well-suited to obtaining organic objects from precisely this period. At first, there was a lot of optimism: tiny seeds would forever solve one of archaeology’s biggest puzzles. At last, we were to know when the transition from Iron I to Iron IIb took place. Mazar of Finkelstein? 970 or 930? Maximalism or minimalism?

Obviously need more radiocarbon samples are needed. To collect these, archaeologists have conducted digs at Megiddo, a site that is exceptionally well-suited to obtaining organic objects from precisely this period. At first, there was a lot of optimism: tiny seeds would forever solve one of archaeology’s biggest puzzles. At last, we were to know when the transition from Iron I to Iron IIb took place. Mazar of Finkelstein? 970 or 930? Maximalism or minimalism?

Unfortunately, things didn’t work out as hoped. That became clear when later press releases started to focus on worthless objects like gold and jewelry, and no longer mentioned what the Megiddo excavation had been about.

But now, the results are there. (Fanfare! Drumrolls! Lights!) Here is the official article.

The disputed transition from the late Iron I to the Iron IIA … falls in the range 985-935 BCE …, meaning that it cannot be decided according to the Megiddo data.

In short: those tiny seeds didn’t solve a thing and one of the nicest, most fascinating, and most important archaeological puzzles remains unsolved. Frustrating perhaps, but personally, I love the prospect of an interesting debate that will continue for a another couple of years.