The March - basics

Roads

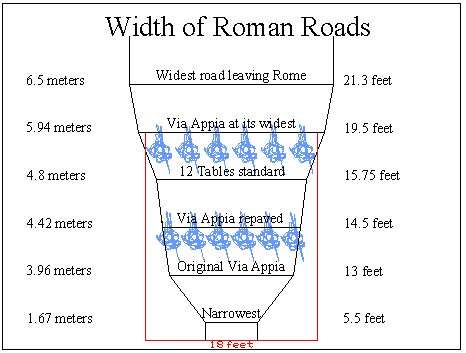

The Roman roads were constructed for military purposes. It is obvious that, whenever possible, the army moved along the roads. Therefore the width of the paved roads determined the width of the Roman column. Most descriptions ignore this factor. Judson, for example, describes the army marching on a 40 foot front. There were no Roman roads that were 40' wide. The illustration below shows some of the established widths of Roman roads.

The illustration to the right shows the widths of roads that I have been able to find cited in various sources. Even in Rome itself, roads were seldom 20' wide. The standard given in the 12 Tables was about 15 feet. Many actual roads were narrower.

The illustration to the right shows the widths of roads that I have been able to find cited in various sources. Even in Rome itself, roads were seldom 20' wide. The standard given in the 12 Tables was about 15 feet. Many actual roads were narrower.

However, most descriptions of the army on the march state that the soldiers marched 6 abreast. The standard spacing is usually given at 3' for each file. Allowing 1 foot between the edge of the road and the lane in which the outside soldier marches requires a minimum road width of 18 feet. This 18' road width is drawn in red in the illustration. The top set of blue figures show a rank of 6 soldiers on 3' intervals and how they would fit into the road widths. The lower set of figures squeezes the 6 men into a width that would fit the Via Appia when it was repaved, 14 1/2 feet. This formation does not seem viable to me in that the actual width of each man, including his gear is 2'6" and the allowed width for each file is 2'7". There is only 3" between the outside man's foot and the edge of the road. It does not seem feasible that six men could march with their gear in that tight a formation.

The conclusion is that the standard description of 6 abreast only works on certain road surfaces. On many roads, some of which were as narrow as 5 1/2 feet, the number of files would have to be reduced and the length of the column extended accordingly.

During the era of conquest the Roman armies ventured into new territory that did not have the fine Roman road system. I have no information about the conditions of those roads but can only assume that they were inferior to the Roman roads, probably more like tracks in many cases. The tidy arrangement of ranks and files and marching units would hardly be appropriate when visualizing the army moving under those circumstances.

Nevertheless, because the usual descriptions specify 6 files I have maintained this in the models and used a road surface of 18' in width to accommodate them. But it should be kept in mind that in many, perhaps even most, cases the army would have had to move on a narrower or more irregular front.

Spacing of the ranks and files

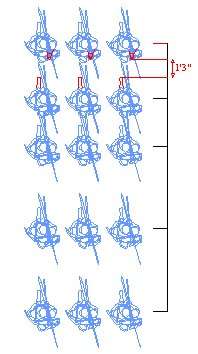

The illustration at the left shows two variations on the spacing of the ranks. The usual standard is 4' between ranks. The top three ranks are on this spacing. The back right feet of the first rank (which would normally be invisible below the packs from this overhead view) and the front left feet of the second rank are shown in red to illustrate the distance between heel and toe. Although the formation looks crowded, there is actually 1'3" between the heel of one person and the toe of the next. This is probably adequate to avoid tripping.

The illustration at the left shows two variations on the spacing of the ranks. The usual standard is 4' between ranks. The top three ranks are on this spacing. The back right feet of the first rank (which would normally be invisible below the packs from this overhead view) and the front left feet of the second rank are shown in red to illustrate the distance between heel and toe. Although the formation looks crowded, there is actually 1'3" between the heel of one person and the toe of the next. This is probably adequate to avoid tripping.

Peddie described the ranks as spaced 6' apart; this is illustrated in the bottom three ranks. The wider spacing seems unnecessary and would extend the column by half again its length, making it even more vulnerable. Therefore the closer spacing seems more probable.

The following models, then, assume roads 18' feet wide and columns of 6 files on 3' centers with the ranks 4' apart. When larger formations are described, 20' was allowed between similar units, 50' between dissimilar units (foot soldiers and pack mules, for example) and up to 100' between cavalry units.

Horses, mules, oxen, carts and wagons

The baggage train took up most of the marching column. A few introductory words about how the Romans transported their baggage is in order.

The Romans had no large draft horses, nor had the horse harness been invented. The yoke system that was developed for oxen was poorly suited for horses. Horses were generally used only to pull light two wheeled carts. Heavy wagons were pulled by oxen. Ancient wagons were designed to be pulled by two animals. Horses and mules can travel at about the same speed as a man, 3 to 4 miles per hours. Oxen travel only about 1 mile per hour.

The Romans had no large draft horses, nor had the horse harness been invented. The yoke system that was developed for oxen was poorly suited for horses. Horses were generally used only to pull light two wheeled carts. Heavy wagons were pulled by oxen. Ancient wagons were designed to be pulled by two animals. Horses and mules can travel at about the same speed as a man, 3 to 4 miles per hours. Oxen travel only about 1 mile per hour.

The preferred method of transport was by pack mule. The advantages of the mule over the horse are described in the Supplemental Information page.

A note about mule packs: Several different mule packs are represented in the illustrations for the march. The pack for the mule carrying the contubernium's tent and equipment is loosely modeled on a photo of a modern reenactment group. The other loads are imaginary. However it seems useful to make them look different to underscore the fact that there would have been quite different loads for different parts of the baggage train. Including different packs in the illustrations encourages thinking about the great variety of material that the army needed to take with it. For that reason the different types of mule loads are shown as they are described.

More information about wagons can be found on the Equipment page.

The army

Roman armies came in many variations over the centuries. For most of the republic the 4 legion army was standard, during the late republic armies became much larger. Under the empire many of the legions became less mobile, serving more as static border guards than as mobile armies. In the late empire the entire army structure changed with much greater weight being placed on the cavalry units. The types and numbers of light infantry (skirmishers) changed over the centuries. The early legions used velites from the legion itself as skirmishers, later armies employed auxiliary skirmishers. The cavalry also changed. The early legions had a small contingent of Roman and allied cavalry, later the cavalry consisted almost exclusively of auxiliaries. Under empire there were periods where there was not much cavalry associated with the armies and then, later, when cavalry took on a much greater role.

Sime the purpose of this section is to create a reasonable model of the army on the march, not to model battlefield tactics, some of these differences in army composition are less important. The critical element is to make an allowance for the various fighting units and their associated baggage and support requirements. Rather than attempt to portray an actual historical army or even period, I have elected to create a fictional army made up of a variety of types of units. This gives an idea of the complexity of the army and also provides some building blocks that could be re-assembled to depict an actual historical army. For example, the army I describe has 4 legions but could relatively easily be expanded to represent one of Caesar's larger armies.

Description of this army: It has 4 legions with centuries of 80 men, 4,800 soldiers plus officers to the legion. Each of the four legions is assigned one Roman ala of 10 33-man turmae, 330 men plus officers. In addition each legion has two centuries or archers and two of slingers as light infantry. There are 8 alae, 2,640 men, of auxiliary cavalry attached to the army as a whole. In addition, there are numerous other units attached to the army including surveyors, medical staff, scribes and servants. The army is commanded by a consul and has a quaestor attached to it. There is one small arrow-shooting artillery piece, a scorpio, assigned for each century, a ballista for each cohort and three onagri for each legion. The pack train also includes several day's rations carried on mules. 4-ox wagons are shown for the onagri. 2-horse carts are shown for the ballistae and as ambulances for the medical unit. Each of these components is described in detail in the following sections.

A 4-legion army was selected because for many centuries that was a standard. It is also easily scaled up or down to more accurately represent later armies of greater numbers. The inclusion of all of the other elements was done to provide some accounting of the entire complex organization that was the Roman army. As will be seen in the final march diagram, the 4 legions took up only a small fraction of the column, most was supply. It is too easy to focus solely on the fighting forces of the army and neglect the enormous support it required. The model tries to inject considerations of some of these support units in reasonable numbers. This army configuration is purely fictional, certainly no Roman army ever had exactly those components. However, I believe it works for the purpose of creating a general model.

Estimates and guesses: To create the model I had to make many estimates and guesses, mostly about the numbers of men or mules: How many fabri? What size baggage train to allow for the general's personal possessions? How many tents for servants? In each case the basis for the estimates are explained in the text. Many of the estimates are pure guesses and I would like to extend an open invitation to readers to offer better estimates of any of these elements.