A 4,000-Year-Old ‘War Memorial’ Identified in Syria, According to New Research

Every so often a news release arrives in my inbox with a discovery that raises my eyebrow. This was one of them:

“What may be the oldest known war memorial has been identified at Tell Banat in Syria, dating to around 2300 BC.”

The news release promotes a research paper appearing in the latest issue of Antiquity, “the international peer-reviewed journal of world archaeology”. It is edited by the Department of Archaeology in Durham University, England and published in partnership with Cambridge University Press, so its credentials are impeccable.

[caption id="attachment_71153" align="aligncenter" width="950"] The White Monument[/caption]

The claim is made by an international team of archaeologists from Canada and the USA who have re-analysed finds from the settlement complex of Banat-Bazi in what is now Syria. The site was occupied nearly 5,000-years-ago.

Just beyond the walls of ancient Banat-Bazi is a large artificial mound today known as the ‘White Monument’ after the white sheen produced by the materials used in its construction. Excavations conducted decades ago established that it was the site of rituals and burials sealed with plaster, which, over time, built up the ‘monument’.

The novelty of the researchers’ work is the claim that “the White Monument was modified around 2400 BC, turning it into what may be the oldest known war memorial.” Backing up the new interpretation was “the construction of horizontal steps over the original mound,” a development which transformed the existing structure.

When finished, it would have looked dramatic in the brown landscape. “This would have looked much like the Stepped Pyramid of Saqqara [in Egypt], and was about the same size, but it was made of dirt, not stone,” said lead author Professor Anne Porter from the University of Toronto, Canada. The huge mound would have been visible for miles around.

The White Monument[/caption]

The claim is made by an international team of archaeologists from Canada and the USA who have re-analysed finds from the settlement complex of Banat-Bazi in what is now Syria. The site was occupied nearly 5,000-years-ago.

Just beyond the walls of ancient Banat-Bazi is a large artificial mound today known as the ‘White Monument’ after the white sheen produced by the materials used in its construction. Excavations conducted decades ago established that it was the site of rituals and burials sealed with plaster, which, over time, built up the ‘monument’.

The novelty of the researchers’ work is the claim that “the White Monument was modified around 2400 BC, turning it into what may be the oldest known war memorial.” Backing up the new interpretation was “the construction of horizontal steps over the original mound,” a development which transformed the existing structure.

When finished, it would have looked dramatic in the brown landscape. “This would have looked much like the Stepped Pyramid of Saqqara [in Egypt], and was about the same size, but it was made of dirt, not stone,” said lead author Professor Anne Porter from the University of Toronto, Canada. The huge mound would have been visible for miles around.

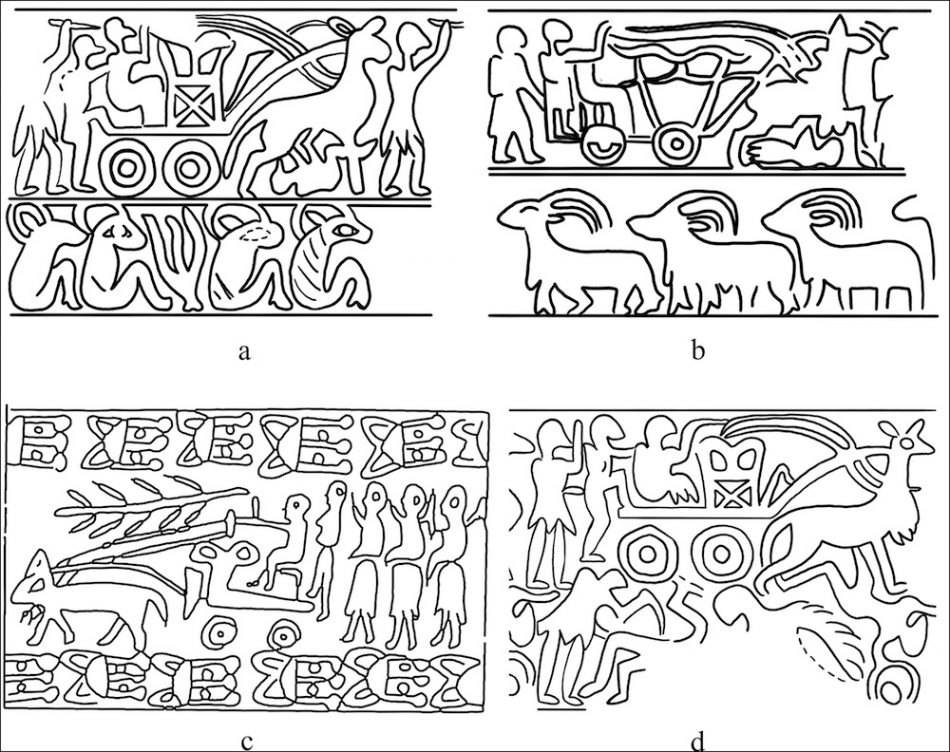

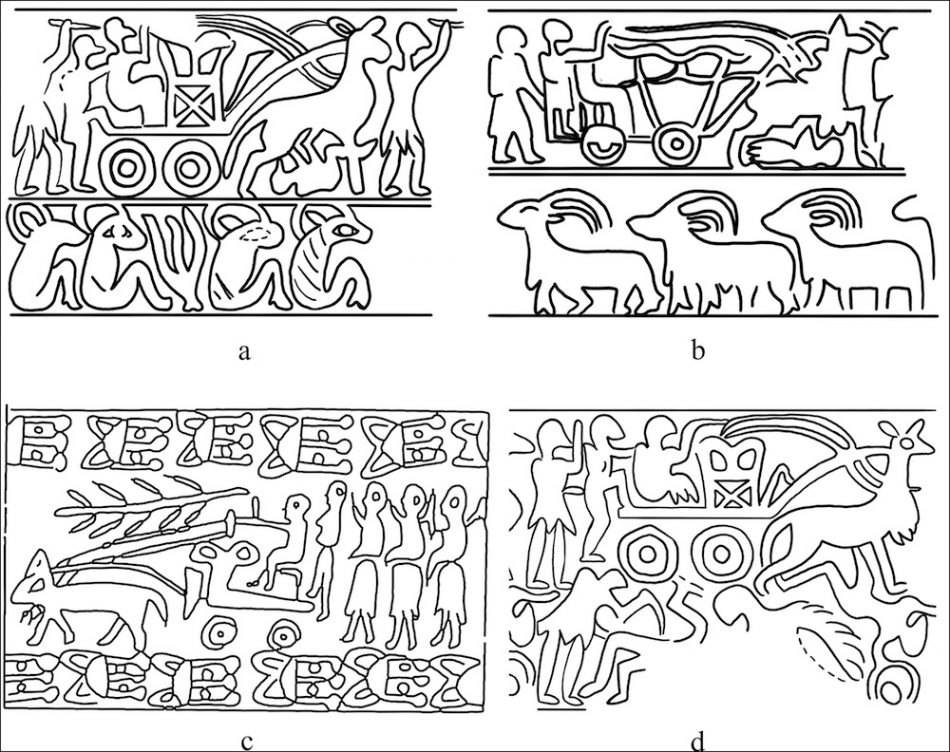

Remarkably, at least thirty people were found to have been buried within these ‘steps’. They included an unusually high number of adults and “older sub-adults” who appear to have been buried along with military gear – slingers’ pellets, and the skins of kunga (a donkey-like breed of equid seen pulling vehicles in ancient art). The researchers found that these individuals appeared to have been carefully deposited, in contrast to the descriptions from the literature of the period, which refers to giant burial mounds of the defeated. The authors of the paper write that there were indications that those interred within the White Monument “were not a vanquished enemy.” Ancient Mesopotamian texts refer to war memorials where the corpses of enemies were piled up, although none have actually been found.

Remarkably, at least thirty people were found to have been buried within these ‘steps’. They included an unusually high number of adults and “older sub-adults” who appear to have been buried along with military gear – slingers’ pellets, and the skins of kunga (a donkey-like breed of equid seen pulling vehicles in ancient art). The researchers found that these individuals appeared to have been carefully deposited, in contrast to the descriptions from the literature of the period, which refers to giant burial mounds of the defeated. The authors of the paper write that there were indications that those interred within the White Monument “were not a vanquished enemy.” Ancient Mesopotamian texts refer to war memorials where the corpses of enemies were piled up, although none have actually been found.

So if not enemy dead, then who were these people? “We recognised that there was a distinct pattern in the burials – pairs of bodies with skins of equids in one part of the monument, single individuals with earthen pellets in the other,” said Prof. Porter. She noted that the pairs buried with kunga “may reflect chariot teams.” Such organisation and specialisation would also suggest also that the military force “was state organised.” Moreover, the team found “it was not a mass grave of those who fell in battle, but the deceased were deliberately reburied in the monument at a later point.”

The researchers theorise that the decision to carefully rebury their own dead in the mound with its new stepped architectural features, possibly along with their military equipment, was a conscious effort by the community to celebrate their warriors. Its 4000-year age would make it the oldest known monument to war dead in the world.

You can make your own determination about the purpose of the mound by reading the paper, ‘”Their corpses will reach the base of heaven”: a third-millennium BC war memorial in northern Mesopotamia?”, in Antiquity Volume 95 No 382 (August 2021), available online at https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2021.58

So if not enemy dead, then who were these people? “We recognised that there was a distinct pattern in the burials – pairs of bodies with skins of equids in one part of the monument, single individuals with earthen pellets in the other,” said Prof. Porter. She noted that the pairs buried with kunga “may reflect chariot teams.” Such organisation and specialisation would also suggest also that the military force “was state organised.” Moreover, the team found “it was not a mass grave of those who fell in battle, but the deceased were deliberately reburied in the monument at a later point.”

The researchers theorise that the decision to carefully rebury their own dead in the mound with its new stepped architectural features, possibly along with their military equipment, was a conscious effort by the community to celebrate their warriors. Its 4000-year age would make it the oldest known monument to war dead in the world.

You can make your own determination about the purpose of the mound by reading the paper, ‘”Their corpses will reach the base of heaven”: a third-millennium BC war memorial in northern Mesopotamia?”, in Antiquity Volume 95 No 382 (August 2021), available online at https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2021.58

The White Monument[/caption]

The claim is made by an international team of archaeologists from Canada and the USA who have re-analysed finds from the settlement complex of Banat-Bazi in what is now Syria. The site was occupied nearly 5,000-years-ago.

Just beyond the walls of ancient Banat-Bazi is a large artificial mound today known as the ‘White Monument’ after the white sheen produced by the materials used in its construction. Excavations conducted decades ago established that it was the site of rituals and burials sealed with plaster, which, over time, built up the ‘monument’.

The novelty of the researchers’ work is the claim that “the White Monument was modified around 2400 BC, turning it into what may be the oldest known war memorial.” Backing up the new interpretation was “the construction of horizontal steps over the original mound,” a development which transformed the existing structure.

When finished, it would have looked dramatic in the brown landscape. “This would have looked much like the Stepped Pyramid of Saqqara [in Egypt], and was about the same size, but it was made of dirt, not stone,” said lead author Professor Anne Porter from the University of Toronto, Canada. The huge mound would have been visible for miles around.

The White Monument[/caption]

The claim is made by an international team of archaeologists from Canada and the USA who have re-analysed finds from the settlement complex of Banat-Bazi in what is now Syria. The site was occupied nearly 5,000-years-ago.

Just beyond the walls of ancient Banat-Bazi is a large artificial mound today known as the ‘White Monument’ after the white sheen produced by the materials used in its construction. Excavations conducted decades ago established that it was the site of rituals and burials sealed with plaster, which, over time, built up the ‘monument’.

The novelty of the researchers’ work is the claim that “the White Monument was modified around 2400 BC, turning it into what may be the oldest known war memorial.” Backing up the new interpretation was “the construction of horizontal steps over the original mound,” a development which transformed the existing structure.

When finished, it would have looked dramatic in the brown landscape. “This would have looked much like the Stepped Pyramid of Saqqara [in Egypt], and was about the same size, but it was made of dirt, not stone,” said lead author Professor Anne Porter from the University of Toronto, Canada. The huge mound would have been visible for miles around.

Remarkably, at least thirty people were found to have been buried within these ‘steps’. They included an unusually high number of adults and “older sub-adults” who appear to have been buried along with military gear – slingers’ pellets, and the skins of kunga (a donkey-like breed of equid seen pulling vehicles in ancient art). The researchers found that these individuals appeared to have been carefully deposited, in contrast to the descriptions from the literature of the period, which refers to giant burial mounds of the defeated. The authors of the paper write that there were indications that those interred within the White Monument “were not a vanquished enemy.” Ancient Mesopotamian texts refer to war memorials where the corpses of enemies were piled up, although none have actually been found.

Remarkably, at least thirty people were found to have been buried within these ‘steps’. They included an unusually high number of adults and “older sub-adults” who appear to have been buried along with military gear – slingers’ pellets, and the skins of kunga (a donkey-like breed of equid seen pulling vehicles in ancient art). The researchers found that these individuals appeared to have been carefully deposited, in contrast to the descriptions from the literature of the period, which refers to giant burial mounds of the defeated. The authors of the paper write that there were indications that those interred within the White Monument “were not a vanquished enemy.” Ancient Mesopotamian texts refer to war memorials where the corpses of enemies were piled up, although none have actually been found.

So if not enemy dead, then who were these people? “We recognised that there was a distinct pattern in the burials – pairs of bodies with skins of equids in one part of the monument, single individuals with earthen pellets in the other,” said Prof. Porter. She noted that the pairs buried with kunga “may reflect chariot teams.” Such organisation and specialisation would also suggest also that the military force “was state organised.” Moreover, the team found “it was not a mass grave of those who fell in battle, but the deceased were deliberately reburied in the monument at a later point.”

The researchers theorise that the decision to carefully rebury their own dead in the mound with its new stepped architectural features, possibly along with their military equipment, was a conscious effort by the community to celebrate their warriors. Its 4000-year age would make it the oldest known monument to war dead in the world.

You can make your own determination about the purpose of the mound by reading the paper, ‘”Their corpses will reach the base of heaven”: a third-millennium BC war memorial in northern Mesopotamia?”, in Antiquity Volume 95 No 382 (August 2021), available online at https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2021.58

So if not enemy dead, then who were these people? “We recognised that there was a distinct pattern in the burials – pairs of bodies with skins of equids in one part of the monument, single individuals with earthen pellets in the other,” said Prof. Porter. She noted that the pairs buried with kunga “may reflect chariot teams.” Such organisation and specialisation would also suggest also that the military force “was state organised.” Moreover, the team found “it was not a mass grave of those who fell in battle, but the deceased were deliberately reburied in the monument at a later point.”

The researchers theorise that the decision to carefully rebury their own dead in the mound with its new stepped architectural features, possibly along with their military equipment, was a conscious effort by the community to celebrate their warriors. Its 4000-year age would make it the oldest known monument to war dead in the world.

You can make your own determination about the purpose of the mound by reading the paper, ‘”Their corpses will reach the base of heaven”: a third-millennium BC war memorial in northern Mesopotamia?”, in Antiquity Volume 95 No 382 (August 2021), available online at https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2021.58