Le Plan de Rome: Ancient Rome in Miniature

[caption id="attachment_71262" align="aligncenter" width="950"][caption id="attachment_71264" align="alignleft" width="950"]Plan cast in bronze at CIREVE Université de Caen ©CIREVE UNiversité de Caen, WikimediaCommons[/caption] For Ancient History 34, our news editor, Lindsay Powell, wrote an article on the work being undertaken by historians to recreate Ancient Rome using the latest computer graphics software. The inspiration for these virtual models is a famous scale model made of plaster in Rome expressly for Il Duce. Yet, there is an older model of the city by a French architect, which is undeservedly less well known. This is the story of Le Plan de Rome.

Circus Maximus in plaster at CIREVE Université de Caen ©WikimediaCommons[/caption]

Circus Maximus in plaster at CIREVE Université de Caen ©WikimediaCommons[/caption]

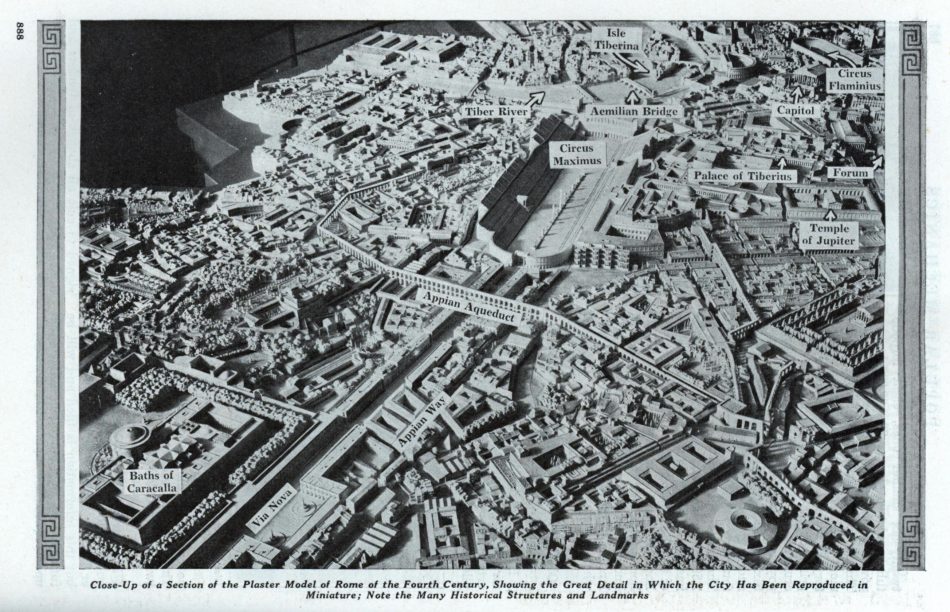

Years ago, as a student, I visited the Art and History Museum at the Parc du Cinquantenaire in Brussels. To my great surprise, it had a model of ancient Rome. The magnificent 1:400 scale representation in 3D of the city had been painstakingly crafted in plaster in astonishing detail by a French architect named Paul Bigot.

Paul Bigot was born on October 20, 1870, in Orbec (Calvados), France. He studied architecture at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris. It was while he was a boarder at the Villa Medici (he was Grand Prix de Rome in 1900), Bigot presented a model that he had made of the Circus Maximus, Ancient Rome’s chariot racetrack. Pleased with his work, he followed it up with an evocation in relief of the entire city!

In 1908, Bigot was invited to exhibit his novel, scale relief map at the International Exhibition in Rome for 1911, in the Archaeology section. Though "still very rough", it was exhibited in a room located in the Baths of Diocletian and was generally well-received by the archaeological world.

[caption id="attachment_71263" align="alignleft" width="350"] Paul Bigot (1870–1942) ©WIkimediaCommons[/caption]

Paul Bigot (1870–1942) ©WIkimediaCommons[/caption]

Bigot made his model in 102 individual sections, that could be assembled and taken apart like a jigsaw. The model was reassembled on April 15, 1913, at the Grand Palais, Paris with the intention of exhibiting it in the Architecture section of the Salon des Artistes Français. Made of plaster it was, however, quite fragile. Around this same time, Bigot had the idea of reproducing his creation in metal. A fund of 80,000 Francs was allocated for the task by Georges Clémenceau, the former prime minister of France. The chosen metal was bronze and the copy was intended for the Sorbonne. The project began but it was interrupted by the First World War.

During the peace that followed, a partial plan in gilt bronze was produced between 1923 and 1925 by ‘Christofle’, the Paris-based goldsmith and tableware company. The bronze model was cast from an original sculpture made by Paul Bigot himself. After numerous exchanges between ‘Christofle’ and Bigot, the exquisite bronze pieces covered with gold were finally delivered to the Institute of Art and Archaeology in Paris in 1932.

In 1925, Bigot had been appointed professor at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris. In 1930, on the Rue Michelet in Paris, he constructed the building intended to house the Institute of Art and Archeology. On the fourth floor of the building, was a large room to display his Plan de Rome. By then it was enormous, measuring 11 x 6 metres, and covering 70 square metres. The following year, he was elected member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts at the Institut de France. In 1933, not to be outdone by the French, the dictator of Italy, Benito Mussolini, commissioned Italian archaeologist Italo Gismondi (b. 1887) to make a larger 1:250 scale model. It is known as the Plastico di Roma Imperiale and it measures 17 x 17

[caption id="attachment_71266" align="aligncenter" width="950"] Close-up of the Colosseum in the scale model of Rome (Plastico di Roma Imperiale) by Italo Gismondi in the Museum of Roman Civilization at E.U.R., Rome ©WikimediaCommons[/caption]

Close-up of the Colosseum in the scale model of Rome (Plastico di Roma Imperiale) by Italo Gismondi in the Museum of Roman Civilization at E.U.R., Rome ©WikimediaCommons[/caption]

metres, covers 240 square metres, and is now displayed in the Museum of Roman Civilization at E.U.R., Rome. Gismondi continued to work on it until 1971, three years before he died. Perhaps on account of its location, Gismondi’s model has received more attention and fame than Bigot’s. Bigot’s model continued to receive praise from noted scholars, including Jérôme Carcopino and André Piganiol. The US publication, Modern Mechanix magazine, which sported the catchy tagline ‘Yesterday’s Tomorrow Today’, reported on the model in its June 1934 issue:

Model of Rome Took Thirty Years to Build After more than thirty years of work, a French architect, Paul Bigot, has completed a stupendous task, the building of an accurate relief map of Rome as it was about the fourth century, A.D., when the city was at the peak of its power. At that time, Rome was the center of as much of the world as was then known. It had gathered the riches of conquered countries and was crowded with temples, palaces, shrines and stadiums. Few of these have escaped destruction but most of the structures have left a trace, either in book or in stone, and M. Bigot carefully studied every source of Roman history before attempting to construct this ancient city as the Caesars knew it. The plaster model of the Eternal City is twenty feet wide and forty feet long and thousands of little blocks represent the monuments and buildings of the past. The scale is one to 400 and three-fourths of the city is represented. Every detail is carefully reproduced so that looking at the model gives the same impression, it is claimed, as though the observer had been able to fly over the Rome of ancient days and view the city from an airplane. The model has been placed for exhibition in the Paris institute of art and archaeology. – Modern Mechanix, June 1934.[caption id="attachment_71265" align="aligncenter" width="950"]

Modern Mechanix news feature.[/caption]

In 1937, Bigot’s scale model moved to the Chaillot Museum in Paris. It was then that Bigot made significant changes to it to include the very latest archaeological discoveries. At the same time, he revisited the idea of transforming the relief into a more durable material. Alas, the project could not be completed. On June 14, 1940, the jackbooted Wehrmacht marched into Paris. Bigot died under the Nazi occupation on June 8, 1942. He was 72 years old.

By being stored at the Institute of Art and Archeology in Paris, a copy of the model survived the Second World War, but not the civil unrest of 1968. Another copy was sent to Philadelphia for an exhibition, but it too was destroyed. Currently, there are only two complete copies of Paul Bigot's Plan de Rome. The original is now housed at Université de Caen Normandie. Bigot had coated it with an ochre varnish, but as the years passed, dust, moisture, and cracking, had caused it serious damage. It was repaired in 1995 at the workshop of the conservator Philippe Langot in Semur-en-Auxois. The second, colourised copy is displayed in the Royal Museums of Art and History, where I saw it in Brussels. As for the partially complete bronze Plan, it is kept in the cellars of the Institut d'Art et d'Archéologie de Paris.

Visitors to the Art and History Museum in Brussels can now inspect the model from a viewing platform, affording a spectacular bird’s-eye view of the city as it may have appeared in AD 320. The model is illuminated by 35 lights to highlight specific buildings and to create different moods. Bringing the experience right up to date, Bigot‘s Plan has been enhanced with digital content accessible using virtual reality (VR) headsets.

Despite all the technological progress, Bigot’s magnificent 3D models in plaster or bronze can still take your breath away. Where the new CG models of Ancient Rome are truly impressive and allow the viewer an unprecedented street-level view, the physical models of the complete city wow the visitor with their sheer scale. Standing above one makes an immediate impact in a way an image on a flat-screen simply cannot. Paul Bigot devoted most of his working life to his reconstructions. Fittingly, the Plan de Rome has since been listed as an ancient monument in its own right.

Lindsay Powell is news editor of Ancient History and Ancient Warfare. He loves scale models of buildings and architectural drawings. Follow Lindsay on Twitter:@Lindsay_Powell

Modern Mechanix news feature.[/caption]

In 1937, Bigot’s scale model moved to the Chaillot Museum in Paris. It was then that Bigot made significant changes to it to include the very latest archaeological discoveries. At the same time, he revisited the idea of transforming the relief into a more durable material. Alas, the project could not be completed. On June 14, 1940, the jackbooted Wehrmacht marched into Paris. Bigot died under the Nazi occupation on June 8, 1942. He was 72 years old.

By being stored at the Institute of Art and Archeology in Paris, a copy of the model survived the Second World War, but not the civil unrest of 1968. Another copy was sent to Philadelphia for an exhibition, but it too was destroyed. Currently, there are only two complete copies of Paul Bigot's Plan de Rome. The original is now housed at Université de Caen Normandie. Bigot had coated it with an ochre varnish, but as the years passed, dust, moisture, and cracking, had caused it serious damage. It was repaired in 1995 at the workshop of the conservator Philippe Langot in Semur-en-Auxois. The second, colourised copy is displayed in the Royal Museums of Art and History, where I saw it in Brussels. As for the partially complete bronze Plan, it is kept in the cellars of the Institut d'Art et d'Archéologie de Paris.

Visitors to the Art and History Museum in Brussels can now inspect the model from a viewing platform, affording a spectacular bird’s-eye view of the city as it may have appeared in AD 320. The model is illuminated by 35 lights to highlight specific buildings and to create different moods. Bringing the experience right up to date, Bigot‘s Plan has been enhanced with digital content accessible using virtual reality (VR) headsets.

Despite all the technological progress, Bigot’s magnificent 3D models in plaster or bronze can still take your breath away. Where the new CG models of Ancient Rome are truly impressive and allow the viewer an unprecedented street-level view, the physical models of the complete city wow the visitor with their sheer scale. Standing above one makes an immediate impact in a way an image on a flat-screen simply cannot. Paul Bigot devoted most of his working life to his reconstructions. Fittingly, the Plan de Rome has since been listed as an ancient monument in its own right.

Lindsay Powell is news editor of Ancient History and Ancient Warfare. He loves scale models of buildings and architectural drawings. Follow Lindsay on Twitter:@Lindsay_Powell

Love ancient history? Want to learn more about the Romans?