Ancient Trans-Saharan Trade

Work is well underway on the next issue of Ancient History, number 52: Roman Africa. We have a good range of articles, from Roman-African relations to the Donatist controversy. So, for this week’s blog, in the spirit of the upcoming issue, I thought I would explore an important part of ancient Africa, trans-Saharan trade.

It is commonly held that trans-Saharan trade did not take off in any meaningful capacity prior to the Islamic conquest in the eighth century AD, as Masonen, for example, wrote: “The regular commercial and cultural exchange between western Africa and the Mediterranean world did not start properly until the 8th century AD” (1997, p. 117). However, there is plenty of evidence to suggest that a complex trans-Saharan trade network existed (see Wilson, 2012; Schörle, 2012). Notably, Herodotus described a series of oases settlements dotting the desert, roughly ten-days walk apart (4.182–185). As Mattingly notes, the existence of these settlements, and Herodotus’ knowledge of them, demonstrate the existence of communication between them (2011, p. 50). Additionally, Herodotus also talks of how the Nasamones, a Libyan tribe, travelled across the desert until they came to a city next to a great river (2.32), “almost certainly to be equated with the River Niger” (Mattingly, 2011, p. 50). Similarly, the Garamantes are said to hunt Ethiopians in their chariots (Herodotus, 4.183).

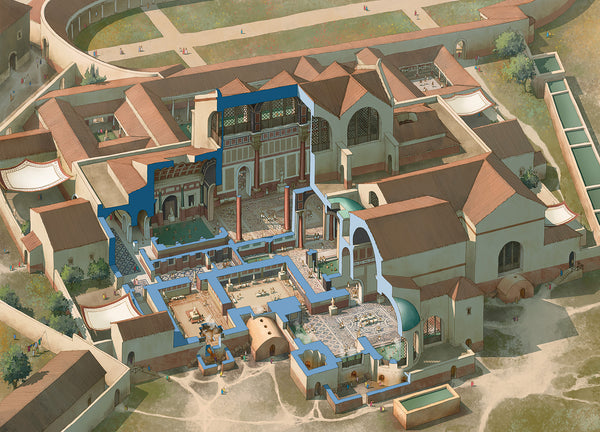

While Lucian describes the Garamantes as tent dwellers and reliant on agriculture (Dipsades 2), other authors refer to their settlements as oppida (Pliny, Natural History 5.36; Ptolemy, Geography 4.6.12), suggesting a proto-urban or urban society. Archaeology has demonstrated that the Garamantes’ capital, Garama (modern Jarma or Germa), was a major urban site with many peripheral and minor settlements, with a population possibly numbering in the tens of thousands (Mattingly, 2011, p. 54). In the area around Garama, the Garamantes “made the desert bloom through sophisticated irrigation methods” (Mattingly, 2011, p. 49). Hundreds of foggaras, underground channels – some 50 m deep – tapping into groundwater, have been discovered, and archaeobotanical evidence suggests that, in the early first millennium BC, the Garamantes were growing wheat, barley, grapes, and date palm. Such foodstuffs were likely among the goods the Garamantes traded with Mediterranean people, as evidenced through the presence of as many as 50,000 Tripolitanian and Italic amphorae, as well as glass (Fentress, 2011, p. 68; Mattingly, 2011, p. 54).

Gold, semi-precious stones, and textiles may also have been among the goods traded, yet the most profitable commodity the Garamantes traded in was likely humans. We have already seen how the Garamantes ‘hunted’ Ethiopians in the fifth century (Herodotus, 4.183). Later, according to Ptolemy, Septimius Flaccus, in the first century AD, accompanied the king of the Garamantes on a southward raid, likely a slave raid (Geography 1.8, 1.10). As Fentress notes, from the fifth century BC onwards, Black Africans increasingly begin to appear in Greco-Roman art in a servile capacity, such as a bronze statuette from Fayyum, dated to the third century BC, depicting a boy with his hands bound behind his back (2011, p. 67). In the second century BC, the Roman playwright Terence could refer to an Ethiopian slave girl as a believable gift (Eunuchus 165–7, 470–1). The Garamantes’ slave trade may have even facilitated the development of the gold tans-Saharan gold trade, with slaves being both a commodity and able to carry other goods, as Fentress notes that the trade did not take off until the fifth century AD (2011, p. 66).

Despite the Sahara’s inhospitable nature – Vitruvius claims that earth from the desert causes crops to fail and die (On Architecture 8.3.24) – it was not an impenetrable barrier. For almost a millennium, the Garamantes were a key link connecting the Mediterranean world and Sub-Saharan Africa. Sadly, it appears that such connections were likely violent, with the Garamantes transporting slaves northwards, many of whom likely died on the way, to satisfy the Carthaginian, Greek, and Roman societies’ desire for slaves.

References:

E. Fentress, ‘Slavers on Chariots’, in A. Dowler and E.R. Galvin (eds.) Money, Trade and Trade Routes in Pre-Islamic North Africa (London, 2011), 65–71.

D. Mattingly, ‘The Garamantes of Fazzan: An Early Libyan State with Trans-Saharan Connections’, in A. Dowler and E.R. Galvin (eds.) Money, Trade and Trade Routes in Pre-Islamic North Africa (London, 2011), 49–60.

P. Masonen, ‘Trans-Saharan trade and the west African discovery of the Mediterranean world’, in M. Sabour and K.S. Vikør (eds), Ethnic encounter and culture change. Papers from the Third Nordic Conference on Middle Eastern Studies, Joensuu June 1995 (Bergen, 1997), 116–42.

K. Schörle, ‘Saharan Trade in Classical Antiquity’, in J. McDougall and J. Scheele (eds) Saharan Frontiers: Space and Mobility in Northwest Africa (Bloomington, 2012).

A. Wilson, ‘Saharan trade in the Roman period: short-, medium- and long-distance trade networks’, Azania 47 (2012), 409–449.