A veteran's sacrifice

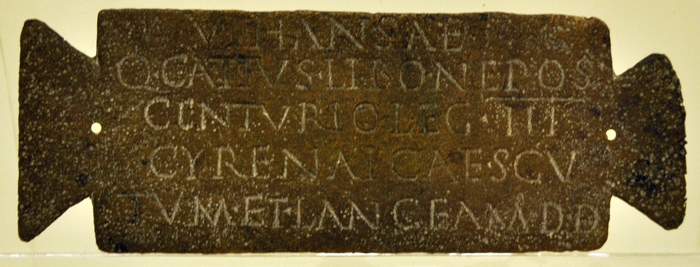

This small piece of bronze, about fifteen centimeters wide, can be seen in the Royal Museums for Art and History in Brussels. If you have never visited them, you should go there, because they have one of the most underestimated collections in the world, including the original statuette of Tintin’s Broken Ear. You will find the bronze object in the department of national archaeology in the basement, because it was excavated in Sint-Huibrechts-Hern, a village in eastern Belgium, just north of Tongeren, the ancient capital of the Tungri. You don’t need to know much about Latin to read the text:

Vihansae

Q(uintus) Catius Libo Nepos

centurio leg(ionis) III

Cyrenaicae scu-

tum et lanceam d(onum) d(edit)To Vihansa

[has] Quintus Catius Libo Nepos,

centurio of the Derde Legion

Cyrenaica, his shi-

eld and spear donated as a gift.

Vihansa is not a common Roman goddess. Her name looks Germanic and may have been derived from two Germanic words, *wīga, “to fight”, en *ansu, “deity”. That her name means something like “War Goddess” or “Lady Battle” is quite plausible, but not proved: the two asterisks indicate that the words are just reconstructions of an early linguistic stage. There is room for some uncertainty.

Still, it would have been fitting that an officer leaves a sacrifice in the sanctuary of a war goddess. Moreover, it’s not a normal present: he laid down his weapons. This was not a common thing for a Roman officer to do. Granted, we have evidence for this type of sacrifice from Greece, where collections such as Olympia show that it was expected that victorious commanders left behind helmets and weapons in sanctuaries. Roman generals are known to have followed this custom.

Another region where arms could be donated to the gods, was Northwestern Europe. The sanctuary in Empel (Netherlands) is an example: at the end of their military career, veterans of Rome’s Batavian auxiliary units visited that place to lay down their old, worn weapons, and sacrifice to Magusanus, who had protected these soldiers.

I think Quintus Catius Libo Nepos did something similar. He had returned to his hometown Tongeren, having served for many years in the Third Legion Cyrenaica. For reasons that I do not know, the excavators of this bronze votive tablet date it to the third century, when the Third had Bosra as its headquarters. That’s a city south of modern Damascus in Syria, and the capital of the Roman province of Arabia. Quintius Catius Libo Nepos must have seen the black, stone buildings of Bosra, must have spent his days off in cities like Damascus, Tyre and Beirut, and must have patrolled along the road to Akaba.

Depending on the exact moment of his stay in the east, Quintus Catius Libo Nepos must have taken part in the campaign of Caracalla against the Parthian Empire (216-217), the expedition of Severus Alexander against the Sassanian Persians (235), the unhappy war of Valerian (253, 260), the campaigns of independent Palmyra, and the lightning campaign of the emperor Carus to Ctesiphon. If our centurio lived at the end of the third century, he may have been present when the fort in the Azraq oasis was built.

Just imagine what Quintus Catius Libo Nepos thought when he laid down his spear and shield in the sanctuary of Vihansa. He had visited Petra, Jerash, Bosra, Damascus, and Palmyra. He had crossed the Euphrates. He had been in Tyre and Corinth. He had seen the emperor. He knew Rome and its monuments. And now he had returned as a wealthy man to his hometown, where even the richest citizens had never traveled beyond Cologne or Lyons. The people who were supposed to be his equals had no idea how much of the world Quintius Catius Libo had seen.