Time, part 7: a world without time

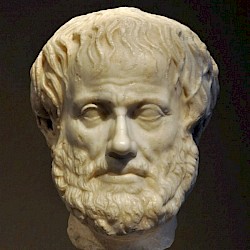

If God is perfect, he cannot change. After all, if he would, he would be imperfect either before or after that change. Now if God cannot change, how can he have created the universe? This was more or less the argument that Aristotle used to prove that the world was not created and, therefore, had to be eternal.

If God is perfect, he cannot change. After all, if he would, he would be imperfect either before or after that change. Now if God cannot change, how can he have created the universe? This was more or less the argument that Aristotle used to prove that the world was not created and, therefore, had to be eternal.

It’s a good point and it took centuries before it was refuted. The most famous treatment is by Augustine of Hippo, who addresses the question what God did before the creation in the Confessions. After having joked that before the creation, God created Hell for people who ask improper questions, he made the simple but profound point that if God created everything, time had been created as well, and that there was no “before” before the creation. Aristotle’s question was devoid of meaning.

It is always easy to make fun of philosophers. “If you read what they thought about women, you become skeptical about what else they have were thinking about” – those kinds of jokes. But we have to admit that Aristotle and Augustine were asking good questions and were, in their mind, boldly going where no man had gone before. Aristotle was one of the first to imagine that the world might not have been created; Augustine’s response runs counter to our intuition.

However, these two men, who were struggling to understand time and its implications, were exceptions. Not many ancient writers really thought about *it (which make the efforts of Aristotle and Augustine even more impressive). It is as if people lived in a world without time.

In one of the late-antique juridical texts – I forget which one – there is a remark that aristocrats ought to have markets on their country estates, because otherwise the peasants would lose too much time to visit the city. It’s one of the few texts that betrays awareness of the fact that time itself had value. You can translate “time is money” into Latin or Greek, but most people would not have understood it.

The rhythms were different, back then. As we have seen in Josho’s article on water clock, the Greeks and Romans accepted that the twelve hours did not have the same length in the winter and summer. The daily rhythms changed with the season – the ancients had no problem with that. They were amused by the Jews, who had a seven day rhythm and had a fixed day of rest, and it was only in Late Antiquity that this became the common rhythm of the Mediterranean world. Until then, the calendar with the festivals dictated when the people could rest, and it was more or less random.

That terrible poetic cliché that, to a lover, time passes slowly when he is waiting for his beloved, and that time passes too quickly when he is with his beloved, is mercifully absent from ancient poetry. There is, except for an occasional scientist, no obsession with minutes or seconds. If you look at tombstones, you will see that people always died when they were precisely fifty, sixty, or seventy years old. Even soldiers, who were discharged after twenty or twenty-five years of service, were not really aware of their age, even though their units must have had some kind of administration. As the example of Mainz shows, they did not know precisely how old they were.

When Alexander invaded India, he said he did it because his ancestors Dionysus and Heracles had been kings of India. When he sacked parts of Persepolis, it was in revenge for Xerxes’ expedition to Greece, which had been a century and a half before. Our sources take this as seriously as more recent events, not distinguishing between the recent and the distant or mythological past. Alexander had no sense of time.

It all changed when the Christians needed to calculate the true Easter date, and the use of a calendar era was no longer something for astronomers. Everyone who had studied the Seven Liberal Arts knew the computus. This created awareness of the depth of time and our modern sense of history.