Thoughts on Matt Damon's Odysseus

By Owain Williams

The first image of Matt Damon as Odysseus in Christopher Nolan’s upcoming adaptation of the Odyssey have been released. The image shows Matt Damon in a grey cloak, red-crested helmet, and decorated vambrace standing before a wall decorated with a fresco. The image has garnered some vocal criticism on social media – what doesn’t these days? – with critics focusing on the helmet, arguing for a boars’ tusk helmet and a more general Mycenaean setting. While these criticisms are valid, to an extent, I feel like they also oversimplify things (again, social media). So, in this blog, I thought I would voice my own criticisms of the image – not just the helmet – and explore the nature of the Homeric epics from the angle of an adaptation.

Firstly, I think it is worth noting that we do not know the context of this image, both in terms of the narrative of the film and in the film’s development cycle. It could be a test image of Damon’s costume, but could be either a still from some point in the film or a purely promotional image. The latter options are more likely, though. An image like this would be officially released unless it was indicative of the final product. As such, I feel it is safe to assume this is how Odysseus will look at some point in the film.

So, what about the helmet? I understand why they have gone with this design. The red crest is a distinct motif of films that the audience will immediately associate with the ancient world, even if only generally. The helmet itself, however, does not conform to an ancient Greek helmet that I know of. It almost feels like it is a design based on Hollywood exemplars of ancient helmets, rather than on examples from archaeology. As numerous users have pointed to on social media, an obvious choice the film could have chosen is the boars’ tusk helmet. Odysseus is actually given such a helmet in the Iliad (10. 260–271), and it is a helmet used in Mycenaean Greece, which many people associate the Homeric epics with, although the epics and the world they describe are distinctly post-Mycenaean. The inclusion of the boars’ tusk helmet in the Iliad is often taken as a genuine survival through the oral tradition of the Trojan War, from the Mycenaean period down to when the poem was finally transcribed in the late eighth or early seventh century BC. However, the problem with this reading, as Hans van Wees has pointed out, is that the passage the helmet appears in is not linguistically old, as one would expect from a Mycenaean element, (2002, p. 19) – some elements of the Homeric epics are linguistically old. What’s more, while the appearance of helmets is usually taken for granted, this helmet is explained in intricate detail, suggesting that, in the context of the Homeric world, it is an exceptional piece of equipment (1994, p. 136). It also, I might add, never appears again in the Homeric epics. It seems it was included in Odysseus and Diomedes’ nighttime escapades precisely because the helmet did not shine, as a bronze helmet would have done. Odysseus was not tied to the boar’s tusk helmet in Greek art, with one vase depicting the precise scene where he would be wearing it – the infiltration of Rhesus’ camp – depicting him bareheaded. Now, this does not mean boars’ tusk helmets were not presence in post-Mycenaean Greece. As Maran writes, “valuable objects and even symbols of kingly power were handed over from generation to generation and could survive the turmoil at the transition between the Bronze Age and Iron Age” (2006, p. 141). That said, I would prefer to see Odysseus wearing a so-called ‘Illyrian’ helmet – named such because of the frequency of early finds of this helmet type from Illyria – which was developed in the Peloponnese, which historical Ithaca had close ties to. Alternatively, it would be fun to see characters wearing a Kegel-type helmet, an even earlier example of Greek helmet than the Illyrian or proto-Corinthian helmet.

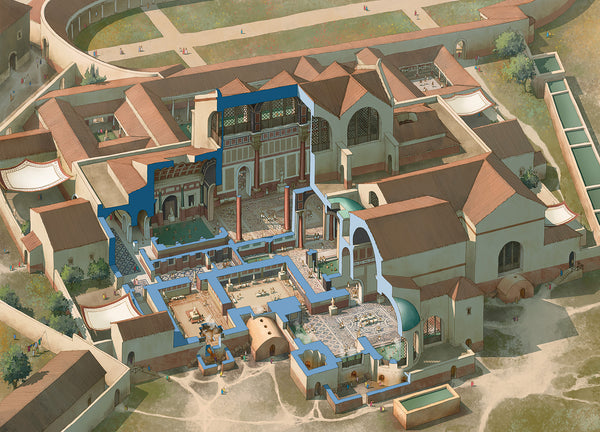

Despite the post-Mycenaean nature of the Homeric epics – the world the poems describe is nothing like the palatial society we know from archaeology and the Linear B tablets, and instead likely reflects the eighth century BC – it appears that the film will utilise Mycenaean motifs in its set design, if the frescoes on the walls behind Matt Damon’s Odysseus are anything to go by. There is no mention of such wall paintings in the Homeric epics, as far as I am aware. Instead, walls are decorated with weapons and armour, and other treasures of bronze, silver, gold, and ivory. In Alkinoos’ palace, for example, which is described as being particularly wealthy, the emphasis is on precious metals, not paintings or wall hangings. Of course, in later centuries, temples, sanctuaries, stoas, and even homes were richly decorated with paintings and mosaics, but I am not sure how appropriate such decorations are for Homeric Greece.

What bothers me more than the helmet or the general aesthetic they seem to be pursuing, however, is how bland it is. The only colour on Odysseus is his crest! His cloak is grey, as is, it seems, his tunic, and his armour is dull. Clothing was one way the Homeric epics marked out men of wealth and power. Additionally, Greek vases (and other artworks) are full of depictions of richly decorated clothing, whether with colour or with intricate patterns. Given the centrality of weaving to the Homeric household, I would be surprised that Penelope and Odysseus’ slaves did not produce such bright, richly-decorated clothing.

The association between the world depicted in the Homeric epics and Mycenaean Greece is not going away anytime soon, despite the academic work done to demonstrate how distinct the Homeric world actually is from Bronze Age Greece. Popular culture tends to present the Homeric world as that of the Mycenaean palaces (see Total War: Troy, for instance), it just makes it stand out from other depictions of the ancient world. That said, had Christopher Nolan gone with a fully Mycenaean depiction of the Homeric world, complete with palaces, boar’s tusk helmets, and cyclopean masonry, I wouldn’t really have minded, even if I would prefer a later, eighth-century-BC style. In fact, I would have applauded the attempt to create a fully authentic feeling for the film. Yet the impression I get from this image is that the art direction has taken elements from throughout the historical record and sprinkled in an element of fantasy. This, itself, however, is not a mark against the adaptation. The Odyssey, after all, is a fantasy. It isn’t meant to be taken as a one-to-one depiction of a historical Greek society, even if many elements match the late eighth or early seventh century BC, because of the different strategies the poet uses in the creation of the poem. Archaising elements make the setting feel like it is in the distance past, such as the near-ubiquitous use of bronze, while fantasising elements to make the world feel like one of heroes, such as the vastly inflated wealth or feats of superhuman strength. This is, of course, only one image. I am excited to see what the film does look like, when it comes out. Christopher Nolan is a good director – certainly better than others who have recently tackled the ancient world – and I believe this will be a good film.

What do you think about Matt Damon’s Odysseus?

References and further reading (all of which are available online on JSTOR or Academia.edu):

J.P. Crielaard, ‘Homer, History and Archaeology: Some Remarks on the Date of the Homeric World’, in J.P. Crielaard (ed.) Homeric Questions (Amsterdam: J.C. Grieben, 1995), pp. 201–288.

J. Maran, ‘Coming to Terms with the Past: Ideology and Power in Late Helladic IIIC’, in S. Deger-Jalkotzy and I.S. Lemos (eds.) Ancient Greece: From the Mycenaean Palaces to the Age of Homer (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2006), pp. 123–150.

I. Morris, ‘The Use and Abuse of Homer’, Classical Antiquity 5 (1986), pp. 81–138.

H. van Wees, ‘The Homeric Way of War: The 'Iliad' and the Hoplite Phalanx (II)’, Greece & Rome 41 (1994), pp. 131–155.

H. van Wees, ‘Homer and Early Greece’, Colby Quarterly 38 (2002), pp. 94–117.

M.L. West, ‘The Date of the “Iliad”’, Museum Helveticum 52 (1995), pp. 203–219.

2 comments

Hi Iain, that is a really interesting perspective! So, you’d say that costume and set design is more a service to the characterisation of both the characters and the setting, something of a shorthand? That would make sense!

I’m a TV/feature film supervising art director and while I love research , we don’t always apply it, because in the words of Tim Harvey( who designed I , Claudius and the Borgias among many others for the BBC) the first production designer I worked with, “We’re not making a documentary, we’re making a drama” and the design is a servant to the drama. As an example I worked on Britannia 3 and we spent £750,000 building a Roman villa based on Nero’s mothers villa and other Pompeian examples, not historically accurate for first century Roman Britain but necessary to convey the power of Rome, the Roman fort was more accurate but the various British dwellings were certainly not all roundhouses (in my defense there is still a debate about post hole interpretation ! } and the Druids dwellings are more fantasy, but Druids are powerful magic users in the show, I’m looking forward to the Odyessy, which is a fantasy anyway,and interested to see what they come up with!