Heroes 4: from Poliziano to Lachmann

Yesterday, I wrote about Angelo Poliziano, the man who realized that ancient sources are sometimes dependent on each other and should be dealt with accordingly: the original source can be used, the secondary text can be eliminated. Poliziano applied this principle also to the medieval manuscripts that had so diligently been copied by countless anonymous monks: realizing that manuscripts could depend on earlier manuscripts, he proposed the elimination of secondary manuscripts. This was the beginning of what is called textual criticism, the study of texts in order to reconstruct their original wording.

Yesterday, I wrote about Angelo Poliziano, the man who realized that ancient sources are sometimes dependent on each other and should be dealt with accordingly: the original source can be used, the secondary text can be eliminated. Poliziano applied this principle also to the medieval manuscripts that had so diligently been copied by countless anonymous monks: realizing that manuscripts could depend on earlier manuscripts, he proposed the elimination of secondary manuscripts. This was the beginning of what is called textual criticism, the study of texts in order to reconstruct their original wording.

Our Greek, Latin, and Hebrew sources are handed down to us in medieval manuscripts, and because it is humanly impossible that a scribe copies a long text without mistakes, our manuscripts contain scribal errors. Throughout the Middle Ages, copiists had often recognized these mistakes and had tacitly corrected them. However, their conjectures were usually pure guesswork. In fact, the medieval scribes contributed to the proliferation of errors.

Poliziano was more systematic in his approach: he compared as many copies as possible and tried to find out which ones were derived from others – in other words, he tried to discover which manuscripts could be eliminated. He could prove that nearly all manuscripts of Cicero’s Letters to Friends were copies of a single, fourteenth-century manuscript which, in turn, was a copy of a text he had seen in Vercelli. Although there were many copies, there was only one ‘archetype’ and only this text could be used. All other manuscripts could be eliminated.

In this case, the archetype still could be studied, but Poliziano realized that this was not always the case. Using all existing manuscripts of Valerius Flaccus’ Argonautica, he established that they all were derived from a lost book in which several pages had been misarranged. All scribes had copied this error.

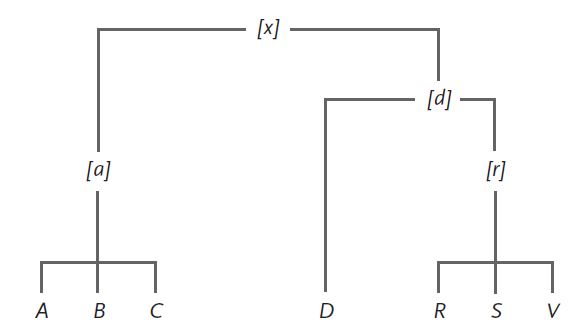

Ever since, textual criticism has been one of the most important parts of the study of Antiquity. It is nothing less than establishing what our data actually are. Modern editions of ancient texts always start with a description of what is called ‘the tradition’: the history of the text, as we can deduce from the manuscripts. Usually, there is a stemma, a family tree, in which the existing and reconstructed manuscripts are shown. Here is an example: the tradition of Herodotus, after elimination of thirty-nine secondary manuscripts.

Only seven manuscripts could not be eliminated and are indicated with capitals at the bottom of the picture. A, B, and C are related – they are a ‘family’ of manuscripts – and must be derived from a lost manuscript a, which can be reconstructed. The same can be said for family R, S, and V, which is derived from r. When we compare r with D, and when we compare the result with a, we can reconstruct archetype x. All known copies are derived from this lost manuscript, which comes closer to Herodotus’ original than any of the existing texts.

In this way, philologists can reconstruct lost originals, turning the ugly fact that there are many variants of ancient texts, into an advantage. Of course, philologists are only happy when they can test their reconstructions, and fortunately, that is possible: among the countless papyri from Egypt, scholars have found fragments of texts that contained precisely the texts as they had been reconstructed. It is a small sample, but sufficient to know that this method is reliable.

Poliziano was the first to grasp the principles, but this method has been developed over the centuries. Tomorrow, I will mention an innovation by Erasmus of Rotterdam. In its present form, the method of textual criticism was created by the Swedish jurist Carl Johan Schlyter (1795-1888), but it has been propagated especially by the German classicist Karl Lachmann (1793-1851) and is therefore often called the ‘Lachmann Method’.

Its most surprising use, by the way, was outside the study of Antiquity: British biologist Charles Darwin realized that all kinds of animals shared common ancestors – archetypes, if you like – and tried to reconstruct a ‘tree of life’ that was analogous to the stemma in a text edition. The theory of evolution is essentially textual criticism transposed to biology.