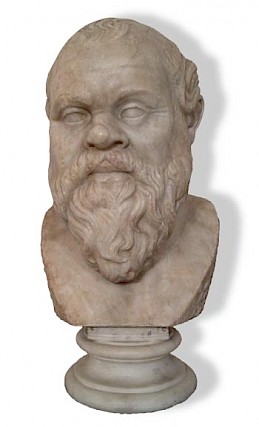

A portrait of Socrates?

Socrates was a Greek philosopher whose work is considered so important that all philosophers who lived before he did are now lumped together as one group: the Pre-Socratics. Socrates was born in Athens around 470 BC and was famously sentenced to death in 399 BC on the pretext of corrupting Athens’ youths.

Socrates never wrote anything himself. Everything we know about him ultimately derives from the work of two important authors who belonged to his inner circle, namely Plato and Xenophon. Other authors add important details, such as the comic playwright Aristophanes and Plato’s student Aristotle. Everything we know about the man – his ‘Socratic’ method, the fact that his father was a sculptor, that his wife was called Xanthippe – derives from these sources.

The ancient Athenians also created portraits of this famous citizen of the city. You’ve probably seen one of these before. Below is a portrait purporting to represent Socrates from the National Archaeological Museum of Naples:

Before the Hellenistic period (i.e. after Alexander’s death in 323 BC), ancient Greek sculptors did not strive to create realistic portraits. They tended to idealize portraits, such as the famous bust of Themistocles. Greek portraits probably did not reproduce the subject accurately. The Greeks were not like the Romans, who excelled when it came to the creation of realistic portraiture.

In fact, this portrait of Socrates seems to evoke the satyr Silenus more than a mortal man. Silenus, according to Greek mythology, was the ancestor of satyrs. Silenus was depicted with the body of a man and the ears and tail of a horse, like most satyrs. But unlike typical satyrs, he was also depicted as older, with a beard, a bald head, and a snub nose; older satyrs were likewise called sileni and modelled after him. Thus, this portrait doesn’t tell us much about Socrates himself. He may have looked sort of like this, but there’s no real way to tell.

Regular contributor Owen Rees reminds me that there is an exchange in Plato’s Symposium where Alcibiades compares Socrates first to Silenus and then to Marsyas, specifically this passage:

And now, my boys, I shall praise Socrates in a figure which will appear to him to be a caricature, and yet I speak, not to make fun of him, but only for the truth’s sake. I say, that he is exactly like the busts of Silenus, which are set up in the statuaries, shops, holding pipes and flutes in their mouths; and they are made to open in the middle, and have images of gods inside them. I say also that hit is like Marsyas the satyr. You yourself will not deny, Socrates, that your face is like that of a satyr.

Furthermore, this statue is a Roman copy of the first century AD. Like many other Roman marble copies, it was based on a Greek original that dated to the first half of the fourth century. This Greek original must have been made shortly after Socrates’ death or perhaps as much as a generation later. This makes it less likely that it is an accurate reflection of the man’s appearance.

In other words, Socrates is an elusive figure. We know of his philosophy and his life only through the writings of those who were associated with him. Likewise, we have this portrait that might not at all resemble what the man actually looked like, but rather reflects popular opinion of him: a satyr-like figure who has left an indelible mark on history.

Edit: Owen Rees’s comments regarding Plato’s Symposium have been added to the body of this blog post.

Further reading

- J.J. Pollitt, Art and Experience in Classical Greece (1972).

- Robin Osborne, Archaic and Classical Greek Art (1998).