March: the whole army

In the previous section the elements that would constitute a single legion were explored. When several legions were assembled into an army there would be some additional units that are described here.

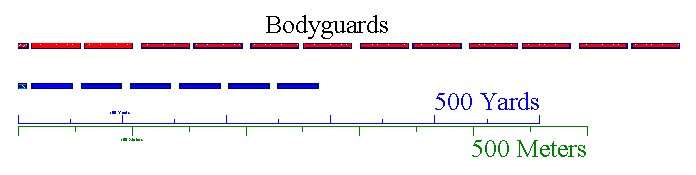

Bodyguards

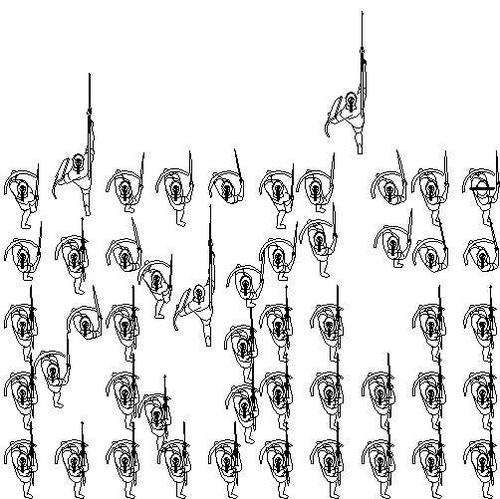

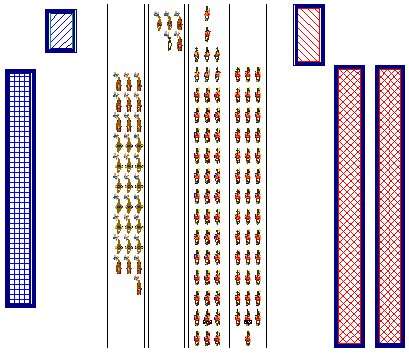

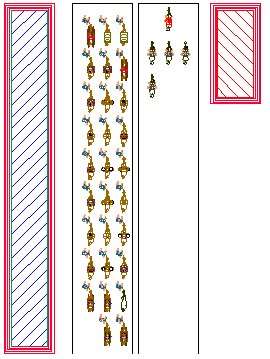

At least by the late republic the commander employed professional body guards made up of paid mercenaries. It seems that the number of bodyguards was not standard but depended on the general. For this model I have used a strength of one cohort, 480 soldiers. The bodyguards are foot soldiers but travel mounted so that they can keep up with the general. Since they are footsoldiers, not cavalry, they are organized into a cohort. The cohort strength, 480 men, is equal to just under fifteen turmae, about 1 1/2 alae of cavalry. The bodyguard unit depicted here is composed of six centuries of 80 men each, as illustrated below.

At least by the late republic the commander employed professional body guards made up of paid mercenaries. It seems that the number of bodyguards was not standard but depended on the general. For this model I have used a strength of one cohort, 480 soldiers. The bodyguards are foot soldiers but travel mounted so that they can keep up with the general. Since they are footsoldiers, not cavalry, they are organized into a cohort. The cohort strength, 480 men, is equal to just under fifteen turmae, about 1 1/2 alae of cavalry. The bodyguard unit depicted here is composed of six centuries of 80 men each, as illustrated below.

The small units at the top represent the commanding officer of the bodyguards, his signiferi, aeneatores and pack train. See below for a detailed illustration.

Following the commander is one century of eighty men. Immediately behind the three aeneatores of the commander is the officer rank (detail below) followed by thirteen ranks of soldiers. The column on the right makes up the balance of the 80 men. See detail below.

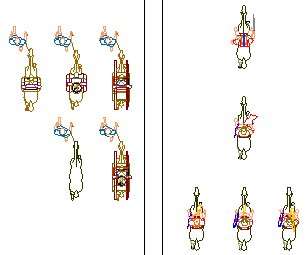

The illustration at the right is a detail of the commander of the bodyguards. The first figure on the right is the commander, followed by a vexillarius and then threeaeneatores (left to right): a cornicen, tubicen and bucinator.

The illustration at the right is a detail of the commander of the bodyguards. The first figure on the right is the commander, followed by a vexillarius and then threeaeneatores (left to right): a cornicen, tubicen and bucinator.

On the left is the commander's baggage: a tent, two mule packs of personal gear, a tent for his servants and his extra horse.

This illustration is a detail of the officer commanding the century, the center figure in the column on the left. He is flanked on his left by a cornicen and on his right by a vexillarius. Behind him and to his right are the ranks of the eighty members of his century, shown here with spears.

This is a detail showing just the baggage train for the century itself.

This is a detail showing just the baggage train for the century itself.

Since the bodyguards would travel in a battle-ready mode, their personal gear would have to be carried by pack mules. I have followed the standard I used above, one mule for each five soldiers. There are nine mules with tents for the eight contubernia of soldiers and their officer. Then there are eighteen mules carrying the personal gear of the century, and finally four tents for the servants.

The illustrations above show only one century of the bodyguards. The entire cohort of six centuries is illustrated below.

The bodyguards escorted the commanding general as a unit. Their march and baggage train formations are shown below. The guards are in red, the baggage train is is blue.

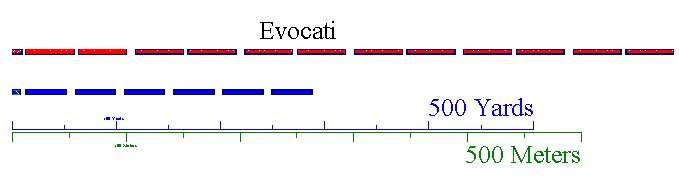

Evocati

The evocati were retired soldiers who came back to serve at the specific request of the commander. They sometimes formed part of the bodyguard, otherwise served as special units at the service of the general. They are described as foot soldiers who each had a horse. I have not found any indication of the numbers of evocati; it seems probable that there was no 'typical' number but that it would depend on circumstances and generals. I used a total strength of one cohort, and used the the same formation and baggage model as for the bodyguards.

Noble youth

(contubernales, comites praetorii)

It was the custom for young men of noble families to accompany the legions as a part of their education process. It is assumed that each youth had a personal servant and tent. The servants could have shared a single tent. For eight youths there would be one additional tent for servants.

Lictors

Under the republic the army would be commanded by either a consul or a praetor. A consul would be accompanied by twelve lictors, a praetor by six. For a consular army of two legions and two allied units the twelve lictors would require two tents, three mules for their personal gear which they could not carry themselves, and one tent for the servants. The lictors are illustrated in the following section, walking, carrying the vine rods over their left shoulders, wearing a plain white tunic.

The general

(Consul, Praetor, promagistrate or imperial general)

The commanding officer of the army certainly had more elaborate accommodations than the other officers. If the general's tent was the size Connolly indicates it would take four mules just to carry the poles and tent leather. In addition the general is allotted twenty personal pack animals and one extra riding horse led by servants, and four tents for servants.

The commanding officer of the army certainly had more elaborate accommodations than the other officers. If the general's tent was the size Connolly indicates it would take four mules just to carry the poles and tent leather. In addition the general is allotted twenty personal pack animals and one extra riding horse led by servants, and four tents for servants.

The pack train did not move with the general. The entourage that would have moved with the general on the march is shown below.

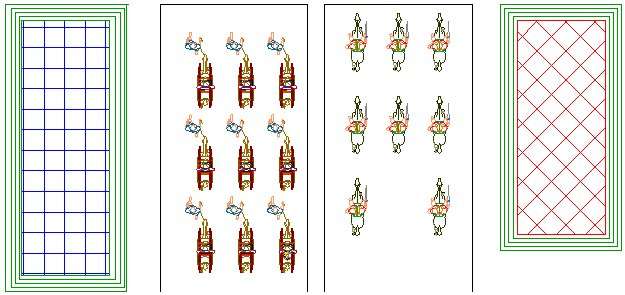

The general's entourage

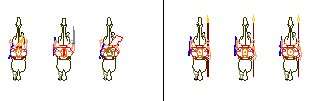

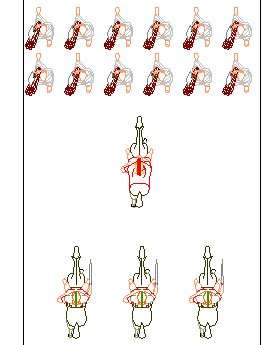

The general, consul or praetor, is described as moving with a large entourage accompanying him. The illustration to the left shows one version of this.

The figures are, from top to bottom:

- one vexillarius

- twelve aeneatores (mounted)

- twelve lictors (walking)

- the general (alone in his rank)

- eight contubernales

- eight mounted scribes (green tunics)

- four mounted servants.

Details of the general's entourage

This illustration shows the general's vexillarius and three of the twelve aeneatores. All are shown mounted so that they could keep up with the general should he choose to move rapidly. I have no particular authority for assigning these men to the general, the only descriptions I have found relate the number of signiferi and aeneatores to the legion. However, it seems reasonable that the commanding general would have also had a vexillum of his own. It seems essential that he would have had a contingent of aeneatores to relay signals to the rest of the army. I chose to give him four tubicines, four cornicines and four bucinatores; one for each of the four legions.

This illustration shows the general's vexillarius and three of the twelve aeneatores. All are shown mounted so that they could keep up with the general should he choose to move rapidly. I have no particular authority for assigning these men to the general, the only descriptions I have found relate the number of signiferi and aeneatores to the legion. However, it seems reasonable that the commanding general would have also had a vexillum of his own. It seems essential that he would have had a contingent of aeneatores to relay signals to the rest of the army. I chose to give him four tubicines, four cornicines and four bucinatores; one for each of the four legions.

The commanding officer of the army may have been a dictator, consul, praetor, promagistrate or imperial general. For this illustration I have depicted a consul with his twelve lictors. A dictator would have had 24 lictors, a praetor only six. Imperial generals would not have had lictors.

This illustration also shows the first three of the eight contubernales who are escorting the general. These nobles are sometimes described as serving as personal aides to the commander so I assembled them here as escorts and companions to him on the march.

This illustration also shows the first three of the eight contubernales who are escorting the general. These nobles are sometimes described as serving as personal aides to the commander so I assembled them here as escorts and companions to him on the march.

In fact it seems that they were used in many capacities and may not have occupied this particularly place in the order of march.

I assigned the general eight mounted scribes. It seems that at least some of the commanders, Caesar, for example, were quite active in their use of scribes to maintain correspondence and keep journals. I show the scribes as mounted so that they could keep up with the general.

I also show four mounted personal servants accompanying the general and his entourage.

I have no authority for either the scribes or the servants,but it seems reasonable to provide some of each as part of the entourage.

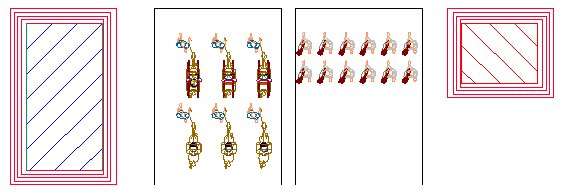

The entourage was also accompanied by the general's bodyguard which was described above. The following illustration shows the general's bodyguard (blue) followed by the general and his entourage (red) in the order of march.

I have allowed 250 feet between the last unit of the bodyguards and the general's entourage. This was done in part to make the units easier to see. But a gap like this would have served the useful purpose of letting the dust settle for the general and his staff.

Quaestor

The army, at least under the republic, had a quaestor assigned to it to keep the accounts.

The army, at least under the republic, had a quaestor assigned to it to keep the accounts.

The quaestor is assigned a large tent the same size as the general's; a four-mule load. He has two mounted personal servants.

The quaestor would have required a number of clerks, but no specific numbers are given. I assigned six clerks: a chief clerk, one for each of the four legions, and one for the auxiliary troops. However I assume that the clerks would be aided by the scribes assigned to the legions.

The pack train consists of four mules for tents, ten mules for the quaestor's personal gear, six mules for the tents of the clerks (one each as an office), seven mules with official documents and equipment (two for the chief clerk, one each for the others), four mules for the servants tents, and an extra riding horse for the quaestor.

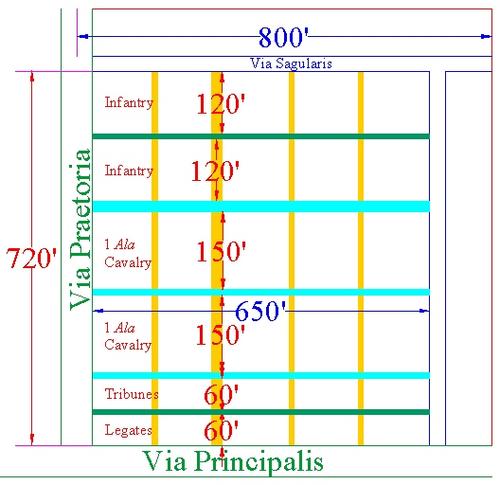

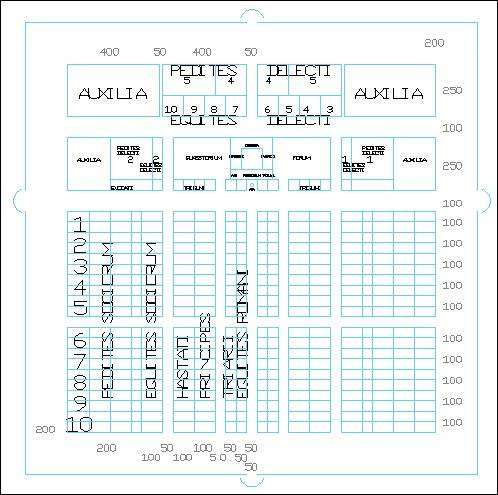

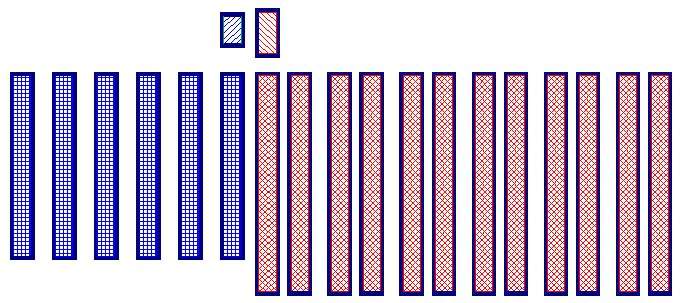

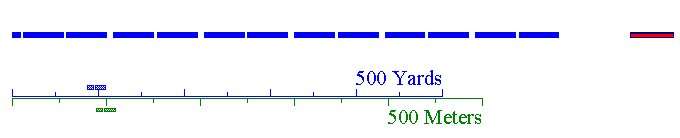

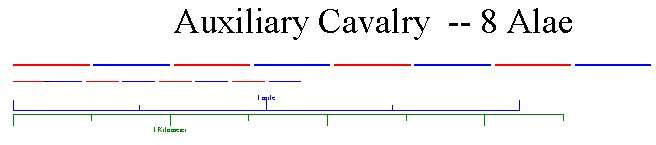

Auxiliary cavalry

The number of auxiliary cavalry varied greatly from army to army. It seems that Caesar may have employed the greatest numbers, 4,000 to 5,000. Other armies may have employed almost none. For the purpose of the model a moderate force of eight alae, 2,640 cavalry is used. There were also four Roman alae (one per legion) for a total cavalry force of 3,960 men.

The illustration above shows the eight alae of auxiliary cavalry assembled altogether. During the actual march the cavalry was used as scouts and to protect the flanks and rear.

Distribution of the cavalry and other mounted units during the march

The mounted soldiers in this army are: four alae of Roman cavalry, eight alae of auxiliary cavalry, one cohort of bodyguards and one cohort of evocati. The sources I have used indicate that various parts of the column were protected by cavalry but do not give unit identifications or numbers. For the purposes of guarding the column I am considering the mounted foot soldiers, the bodyguards and evocati, as cavalry. The mounted units are distributed: Roman cavalry: our alae: one to the vanguard, one as guard for the officers, two to the army equipment and supply baggage; auxiliary cavalry: eight alae: one to the scouts, one to the vanguard, two to the rearguard, two to each flank; evocati: to guard the officers baggage train; bodyguards: to guard the general. This arrangement puts three alae in front of the column (one with the scouts, two with the vanguard), two on each flank and two with the rearguard. It distributes the remaining three alae and the two mounted cohorts at intervals along the column of march.

Iron supply, forge and smithing

The army in any extended campaign would have to provide for the repair and replacement of its weapons. The wood parts could be manufactured from materials found through forage or manufactured on site but iron would have to be either captured from enemy stockpiles, recovered from broken Roman weapons or recovered enemy weapons, or drawn from a supply taken with the army.

This is highly speculative but it does seem likely that the army would take some supply of bronze and iron with it and not rely solely on recovered or found supplies of these essential materials. Each soldier must have carried a minimum of ten to fifteen pounds of metal in armor and weapons. In addition there would be tools, parts of harnesses, artillery fittings, arrow points, sling shot (often made of lead).

An army of roughly 20,000 soldiers would carry, then, something like 200,000 to 300,000 pounds of metal weapons and tools. If as little as 1% of the total weight of metal were taken as a reserve that would be 2,000 to 3,000 pounds. With an average mule-load of 200 pounds it would take a train of ten to fifteen mules.

The repair of weapons would require a small forge and smithing tools. I have not been able to find any information on portable Roman forges. Given the difficulty of wheeled transport, the ideal forge would be carried by mules. It may be possible that a simple portable forge could consist of a dozen or so fire bricks and a bellows. The loose bricks and bellows could be carried on a single mule, the smithing tools on another. A small 200 pound anvil could consist of two or more parts that, when disassembled, could be loaded another mule. Thus a very small, primitive, but workable blacksmith setup could be transported on as few as three mules.

If the forge consisted of these small parts -- bricks, small anvils, tools -- it would look much like any other mule load. I have no information about other types of forges that could be wagon-loaded and transported with the army. Because of the lack of information about the forge I have not made an allowance for it in either the pack mules or in the wagons associated with the legion. Since each legion has a supply train of 288 mules, over a thousand for the whole army, it seems adequate to assume that some of these supply train mules were used to transport the necessary quantities of metal and materials for portable forges.

Spoils of war

The spoils of war figured large in the army's activities. Some campaigns netted enormous quantities of precious metals, objects of art and slaves. The quantity of spoils actually accompanying an army in the field would be highly variable: none at the beginning of a campaign, perhaps a great deal at certain times. Some of the booty would have been transported to secure forts in rear areas. At some times, certainly, the acquired spoils would have had to travel with the army itself. It is likely that an important part of the spoils of war would be the transport necessary to move it -- wagons, horses, mules. Spoils did not constitute a regular part of the army as it moved so no special allowance for them has been made in the baggage train.