The joy of history (1)

I don’t remember the date, but it was at least an hour past midnight… no, this story needs a different beginning. For some time, my former teacher Bert van der Spek and I had been trying to understand the portents surrounding the death of Alexander the Great. They are mentioned in several Greek sources (Arrian, Diodorus, Plutarch, Appian), and Bert had already argued that at least one of the Babylonians involved, a man called Belephantes by Diodorus, might perhaps be identical to a Babylonian astronomer named Bel-apla-iddin. Much of the Greek stories seemed plausible, but what celestial omen predicted Alexander’s death?

I don’t remember the date, but it was at least an hour past midnight… no, this story needs a different beginning. For some time, my former teacher Bert van der Spek and I had been trying to understand the portents surrounding the death of Alexander the Great. They are mentioned in several Greek sources (Arrian, Diodorus, Plutarch, Appian), and Bert had already argued that at least one of the Babylonians involved, a man called Belephantes by Diodorus, might perhaps be identical to a Babylonian astronomer named Bel-apla-iddin. Much of the Greek stories seemed plausible, but what celestial omen predicted Alexander’s death?

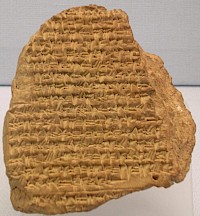

We know a lot about Babylonian astrology. We have the Astronomical Diaries, which contain observations and events that appeared to have been predicted, and a catalog of portents, Enûma Anu Enlil . They are two sides of one project: if something unusual happened in the skies (say, a lunar eclipse), one could check in the catalog what that meant (the death of a king within 100 days). The Astronomical Diaries are the empirical foundation of the catalog.

Bert had already identified some of the sections of the catalog that were relevant to understand how the ancients would have understood the lunar eclipse on 20 September 330, which took place before the battle of Gaugamela. Here is the explanation from Enûma Anu Enlil:

If on either the 13th or 14th Ulûlu the moon is dark; the watch passes and it is dark; his features are dark like lapis lazuli; he is obscured until his midpoint; the west quadrant - as it covered, the west wind blew; the sky is dark; his light is covered.

[The significance is:] The son of the king will become purified for the throne [because the king is dead] but will not take the throne. An intruder will come with the princes of the west; for eight years he will exercise kingship; he will conquer the enemy army; there will be abundance and riches on his path; he will continually pursue his enemies; and his luck will not run out.

After this omen, the Persian army, which consisted of recruits, must have been heavily demoralized; and there is much evidence to confirm this. So, Bert had found a beautiful match between ancient astrology and historical events. To find out which celestial omen had predicted Alexander’s death, however, proved to be more difficult. After a year, neither Bert nor I had been able to find out anything. He had checked the tablets countless times, I had been looking at my computer planetary endlessly, but not a single bad omen, as mentioned in Enûma Anu Enlil, was available.

**

I don’t remember the date, but it was at least an hour past midnight. I was again checking the translated texts and the list of stellar omens. There was no eclipse in June 323, when Alexander died. The next eclopse was in the autumn, eight solar years after Gaugamela. And then, lightning struck: we had been searching in the wrong direction. We had been looking for a portent of death , but should have been looking for a text about the length of Alexander’s reign - in the section above, “for eight years he will exercise kingship”. We had had the solution on our desks for at least a year. I was overcome by a feeling of immense happiness.

I opened a bottle of wine, lighted a cigar, and wrote an e-mail to Bert, who wasn’t sleeping either, and immediately made a phone call. During the conversation, I realized how ridiculous it actually was: two grown-up men, discussing a piece of clay twenty-three centuries old, in the middle of the night.

It’s this experience, the lightning strike and the immense happiness when you realize that you understand the past, that explains why people study history. It can be pretty sensational to discover things. James Joyce would have called it an epiphany. This sensation is also the justification of their activity. The question “why do you study the past?” is as ridiculous as “why do you like to sit in the garden?”, “why do you play chess?”, “why do you go to the movies?” or “why do you like mountaineering?”

History is nice, it is fun. That is enough. There is no need to use it for a practical purpose. Of course this does not explain why our governments pay money for historians. That needs another justification.

Literature

- R.J. van der Spek, “Darius III, Alexander the Great and Babylonian scholarship” in: Achaemenid History 13 (2003), 289-346.