Power and Punishment the Roman Way

A bust depicting Sulla. Currently in the Glyptothek Munich. © Wikimedia Commons

Today's blog post will discuss Roman punishment, which accompanies the feature, 'Civis Romanus Sum', written by our news editor, Lindsay Powell, for Ancient History Issue 39. The issue is about to go to the printer so stay tuned to pick up your copy and read his fantastic article!

Researching my feature article ‘Civis Romanus Sum’ for issue 39 of Ancient History reminded me of how ever-present the threat of punishment was in the lives of people in Republican and Imperial Rome. Abusing political power or committing a crime had very severe, often immediate, consequences – unless, that is, the accused could utter the Latin words for ‘I am a Roman citizen’.

Power to Command

In the Roman political and legal system, chief magistrates (consuls, proconsuls, praetors, propraetors, military tribunes with consular power, and dictators) were entrusted by the People with a ‘special command’ (imperium), which meant having legal power over armed men and the right to use them. It is the origin of our word ‘empire’. A Roman magistrate was required to exercise his imperium responsibly within the defined limits of his ‘duty’ (provincia), from which we derive ‘province’. His power – and it was always a man – lasted a year, or for the permitted duration of the assignment. At the end of the term, he was accountable for any misdemeanours incurred while in office. Officials could be, and indeed were, prosecuted for abuses, as the example of provincials bringing a case against former propraetor of Sicily, C. Verres, demonstrates (which I discuss in the article quoting from Cicero’s trial speeches, In Verrem). Inevitably, there were pressures to extend these set limits and good reasons were made by those asking for the changes. Cn. Pompeius Magnus (AKA Pompey the Great, 106–48 BC) was the first Roman to be granted imperium that exceeded a year. The Lex Gabinia of 67 BC gave him three years in which to deal with pirates located in the Eastern Mediterranean who were menacing coastal communities and shipping in the region. It gave him command over all other Senate-appointed proconsuls and propraetors from the coastline to 50 miles inland across a broad swath of territory covering several provinces. He succeeded in his mission – and also became very rich doing it. However, the law set a precedent.

Marcus Junius Brutus Denarius. 54 BC. LIBERTAS, Head of Liberty right / Consul Lucius Junius Brutus, between two lictors, preceeded by accensus, all walking left, BRVTVS in ex. Syd 906, Cr433/1, Junia 31 © Carlomorino, Wikimedia Commons

Marcus Junius Brutus Denarius. 54 BC. LIBERTAS, Head of Liberty right / Consul Lucius Junius Brutus, between two lictors, preceeded by accensus, all walking left, BRVTVS in ex. Syd 906, Cr433/1, Junia 31 © Carlomorino, Wikimedia Commons

Being able to point to the Lex Gabinia was very helpful to Augustus (63 BC–AD 14). From 27 BC on, his power (termed imperium proconsulare) to run affairs in his assigned provincia was granted by the Senate for five years (a period called a lustrum). In 23 BC, it was expanded, as imperium proconsulare maius, to supersede the powers of other proconsuls and propraetors appointed by the Senate, and even extended into the city of Rome. In 19 BC, it was further combined with the religious auspicia publica, which was required for the full and valid execution of command since no public act could be undertaken without first reading the auspices. His summum imperium auspiciumque meant that Augustus had power to enter all of the provinces at will, both imperial and senatorial, for purposes of peace or war. He achieved what his adoptive father, Julius Caesar, had not, and lived. When his imperium expired, it was renewed again and again until his – natural – death.

Dictatorship

The exceptional power of dictatorship, which superseded other magistrates’ imperium, was an all-encompassing power granted to just one man to deal with an existential threat to the Roman state. It expired when the matter was resolved, or after six months. Among the famous men holding the dictatorship was L. Quinctius Cincinnatus (c. 519–c. 430 BC). In 458 BC, while he was tilling his fields, Cincinnatus received the news that he had been given the emergency executive power. Having defeated the Aequi, he returned to his plough. Remarkably, Cincinnatus was granted the dictatorship again in 439 BC, this time to deal with a plot concocted by a Roman plebeian. Not a man to let the power go to his head, he resigned it again at the appointed time. L. Cornelius Sulla (139-79 BC) was another famous dictator. He was appointed under the Lex Valeria of 82 BC, which imbued him with constituent, legislative, military, and judicial power and, for the first time in Rome’s long history, without a time-limit to his dictatorship, setting another dangerous precedent. The award of the power of dictatorship for life (dictator perpetuo) to C. Julius Caesar (c. 100-44 BC) made him king (rex) in all but name. It was a key reason for his assassination: awarded to him on 26 January (or 15 February), he was lying dead in a pool of his own blood by the Ides of March. After this horrific event, the power of dictator was finally abolished.

Relief of a lictor. Garden of Museo archeologico a Verona © Wikimedia Commons

Citizens’ Rights

The Romans feared deeply that those holding power would abuse it. They enacted laws to ensure that due process was observed, and to protect people with citizenship (civitas) from bodily harm from bad actors. There were good reasons to be fearful. Corruption was endemic during the Republican Period. Each magistrate had a complement of lictores: each consul had 12, proconsul 11, praetor 6, and propraetor 5, while a dictator had no fewer than 24! It was a fearsome bodyguard, each man armed with an axe in a bundle of rods, bound together with a leather strap, called the fasces; Benito Mussolini adopted the iconic device for his party of Fascisti in 1919. These were the instruments Roman magistrates used for carrying out capital punishment: beating, flogging, or beheading. The Lex Valeria of 509 BC required public trials for Roman citizens in cases where the defendant faced scourging or the death penalty and, instead of facing the consuls – who might have vested interests in the verdict – provided for the right of appeal directly to the Roman People (ius provocatio ad populum). The second century BC Leges Porciae ended summary executions of Roman citizens living abroad in the provinces and permitted guilty citizens to escape capital punishment through voluntary self-exile. It seems like a lucky escape, but it is a measure of how highly the Romans viewed participation in their res publica: banishment from the Commonwealth was a humiliation, which damaged a man’s public standing (dignitas). Through the years of the Republic, these rights also covered Roman citizens in the army or on official service outside the city of Rome. Under the principate system, beginning with Augustus, the emperor became the supreme court of appeal. Paul of Tarsus (AKA St Paul, c. AD 5–c. 64/64) appealed to the procurator in Caesarea to let him have his ‘day in court’ (which I discuss in the article quoting Acts of the Apostles 22-25). He fully expected Emperor Nero in Rome to adjudicate his case. As a citizen, Paul was allowed to board a ship and sail to the Eternal City.

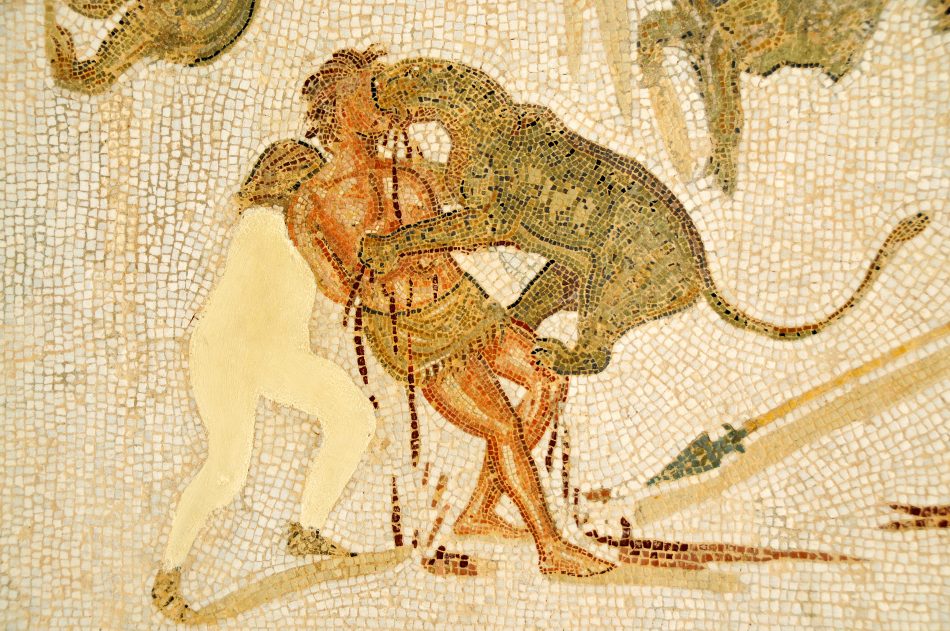

Leopard attacking a prisoner in an amphitheatre spectacle in a Roman mosaic (late 2nd century AD). © Dennis Jarvis, Wikimedia Commons.

Citizens and Non-Citizens

As the Romans annexed territory, conquered people became subjects. The majority of people in the Roman Empire were free-born, non-citizens or ‘foreigners’ (peregrini) as the Romans regarded them. They were covered by a body of ‘law of peoples’ (ius gentium), which did not confer many of the rights and protections of the ‘law of citizens (ius civile). In criminal cases, non-Romans had far fewer protections than full-citizens. To ensure they gave truthful testimony in a criminal trial, the accused could expect to be beaten, flogged, or scourged. Slaves were routinely tortured to extract confessions or witness statements. Found guilty in a capital case, a non-Roman or slave could face imprisonment (in a dark, dank place), or condemnation to a public death in the arena (whether ad bestias or execution by beheading), or in extreme cases (such as Spartacus or Jesus of Nazareth) by crucifixion. Roman justice could be very harsh. Civis Romanus sum were the three most powerful ‘safe words’ a Roman could utter in public. When called for, they could save him from a terrible beating – or even an untimely death. In AD 212, many more people could utter this vital phrase when Emperor Caracalla (AD 188–217) issued a game-changing edict, the Constitutio Antoniniana, which widened the franchise to all freeborn subjects.

Lindsay Powell is news editor of Ancient History and Ancient Warfare magazines. His latest book is BAR KOKHBA: The Jew Who Defied Hadrian and Challenged the Might of Rome (Pen and Sword Books, 2021).

Loved this article? Want to learn more about the ancient Romans?