An Ancient Military Valentine – part 3

(Continues on from part 2)

The outcome of the battle of the Sagra River was apparently announced simultaneously at Sparta, Athens and Corinth on the day the battle was fought (Justin Epitome 20.3.9) whereas Cicero (De Natura Deorum 2.6) and Strabo (6.1.10) only mention it being announced at the Olympian Games on the day it was fought (this gives us some clues as to a possible year in which the battle was fought).

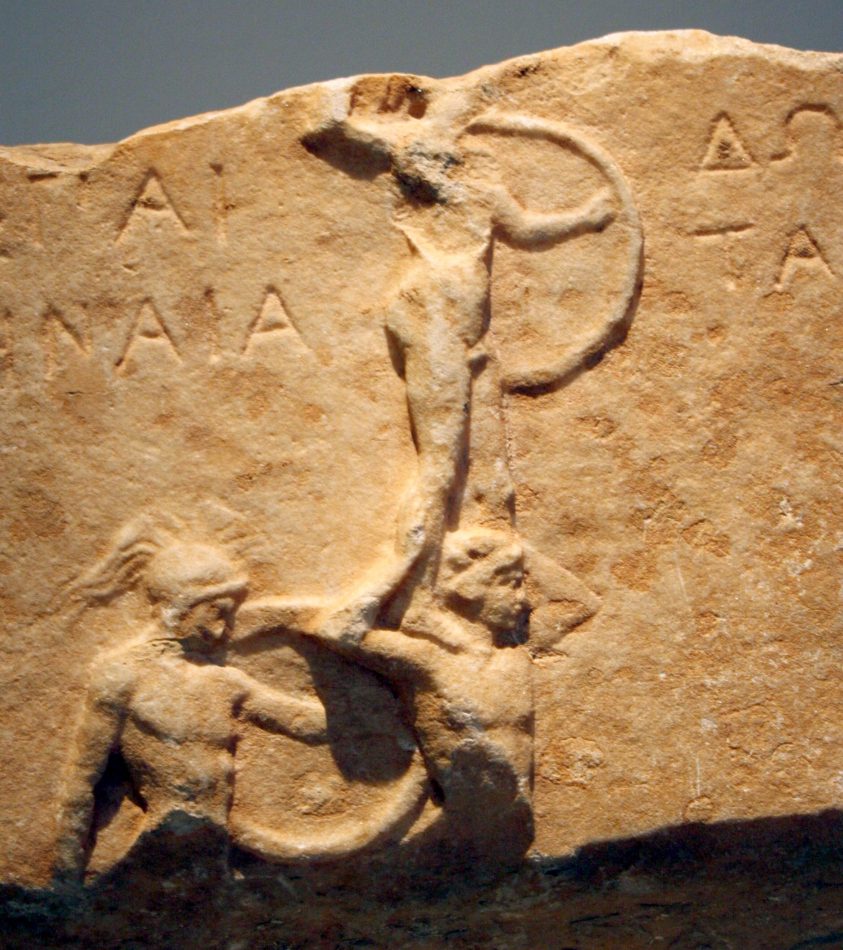

The rape of Hilaeria and Phoebe on a 2nd century Roman sarcophagus now in the Vatican

The rape of Hilaeria and Phoebe on a 2nd century Roman sarcophagus now in the Vatican

The battle of the Sagra River was fought in modern-day Calabria in the toe of Italy, between the forces of several Greek colonies. Its exact date and location are still matters for debate. 15,000 Men from Epizephyrian Locris and Rhegium faced 120,000 men from Croton (in some versions the disparity between the numbers is even greater). The battle was, however, an unexpected victory for the massively outnumbered forces of Locris and Rhegium. At the height of the battle, the Dioscuri were seen fighting on the wings of the Locrian and Rhegian army (Justin Epitome 20.3.8). Before the battle, the Locrians had appealed to Sparta for help – it had been refused save for the advice that the Locrians should look for help from the sons of Tyndareus (Diodorus 8.32.1). They did just that and, after their victory, they set up a shrine to the twins on the site of the battle (Strabo 6.1.10). According to a fragment of the historian Theopompus, whose Philippica is preserved in the Suda (s.v. ‘Phormion’, FGrH 115 F392), Phormion fought in the battle. The association of the battle with Phormion, an appeal to Sparta for help, and the intervention of the Dioscuri, not to mention the association of Phormion and the Dioscuri from an independent story, make for intriguing intersections.

Pyrrhic Dances

Pyrrhic Dances

Photo (right): Pyrrhic dancers in hoplite equipment on a statue base from approximately 375 BC now in Athens - photo by Giovanni Dall'Orto

In addition to their association with horses and cavalry, sailors, and epiphanies, the Dioscuri were also associated with military reform and innovation, especially the Pyrrhic Dance (the pyrriche), encouraged as a form of military drill for hoplites (see my article in Ancient Warfare 14.3). The unlikely victory of the Locrians and Rhegians at the Sagra was memorialised in a saying, used down to Cicero’s time: “Truer than the result at Sagra”, as a means of establishing a true if incredible, unexpected, and unbelievable result (De Natura Deorum 3.5). One reason for the victory may have been that the Locrians and Rhegians were trained in the 'new-fangled' style of Hoplite warfare, with which they defeated their numerically superior foe. The association of the battle with the Dioscuri and the Spartans (famed for their adoption and perfection of hoplite drill) make this association attractive. What is more, if Phormion travelled from Sparta to Italy, he may have acted as an early hoplomachos, a drill master of hoplite manoeuvres. Such men were used later by other cities to train their men in hoplite formations and manoeuvres. And Sparta was particularly associated with such figures (see Wheeler’s ‘The Hoplomachoi and Vegetius' Spartan Drillmasters’).

Phormion's travels

The association with Phormion is interesting for another reason as well. He may have travelled to Cyrene immediately after the battle. Theopompus’ version of events states that Phormion was from Croton (instead of Spartan and not associated with Locris at all – this association seems incorrect) and was wounded in the battle. The wound was slow to heal, but Phormion received advice from an unnamed oracle to travel to Sparta. The oracle told him that the man who would heal him, would invite him to dinner upon his arrival. Arriving at Sparta, Phormion was indeed invited to dinner. Theopompus' fragment then suggests that, as he was celebrating the Theoxenia (a festival to honour the Dioscuri), he was summoned by the Dioscuri to Cyrene. There he arose holding a stalk of silphium. Theoxeny involved gods roaming the earth in disguise (Odyssey 17.485-488) and then being given or refused hospitality by a mortal. It is, therefore, possible that Pausanias’ story is a version of this theoxeny, and the link between Phormion and the Dioscuri. It is also possible the two stories are separate and, in fact, compatible. The link between Phormion and the Dioscuri is strengthened if we accept both stories as separate incidents rather than independent and different versions of only one story. The granting of hospitality usually resulted in reward, and failure to give it in punishment. Theopompus’ version (where Phormion is rewarded) certainly seems to make Platt’s idea (p. 250) that the story in Pausanias is of Phormion being punished for not recognising the Dioscuri much less likely (see also Nicholson’s The Poetics of Victory, pp. 138-139). This would seem to be the case despite the abduction of Phormion’s daughter. That is clearly not intended as punishment, neither in the Pausanias version (with the silphium left behind) nor in the (later) Theopompus version where Phormion was summoned to the Dioscuri in Cyrene (to heal his battle wound). What is more, a comparison with the fate of Scopas (whose whole family was killed along with Scopas himself) and Pentheus (who was torn apart by the daughters of Cadmus) shows Phormion suffered no similar punishment. The association of Phormion’s involvement with Croton, and not Locris and Rhegium in Theopompus’ version is troublesome. On the other hand, the Locrian appeal to Sparta for help and the Dioscuri appearing on their (victorious) side make the Spartan Phormion’s association with them, and not with Croton, more plausible. The association with military training and reform (which brought the victory) strengthens that association. Perhaps the hospitality given to them by Phormion was rewarded at the Sagra River and then Phormion was summoned to Cyrene after he was wounded as a similar reward. Check back tomorrow, for a turn towards Saint Valentine!