Alternatives to 300, part 1: Three

Last year, I wrote a series of blog posts about the movie 300 (2006), and also tangentially mentioned Frank Miller’s graphic novel, which the movie was based on. (There are three posts in all, which you can read here, here, and here.) Miller based his book on the 1962 movie The 300 Spartans, which he saw as a child.

Miller seems to have read some of the original sources – there are lines taken directly from Herodotus – and perhaps a few books on Greek warfare (apparently the wrong ones, but that’s a different story). Much of 300, however, is invented specifically for the book. Both the Persians the Spartans, for example, are little more than caricatures. The movie ramps it all up to eleven and adds even more fantastical elements, such as an armoured rhino and a monstrous Persian executioner.

So, in short, I wouldn’t recommend that you read Frank Miller’s 300 for its historical accuracy. But are there any comic books that cover, more or less, similar ground and that at least try to be more historically accurate? The answer is ‘yes’, fortunately. Today, I want to talk about Three, published in 2014 by Image Comics. The book was written by Kieron Gillen, illustrated by Ryan Kelly with colours by Jordie Bellaire.

Three

The book starts out in ‘Lakonia, Greece’, where we are introduced to the helots, the subjugated population of Messenia. Text on the second page of the comic book proper explains that they are ‘beneath slaves’, who ‘bear the state’s fetters.’ Laconia itself is characterized as ‘a land where men are most enslaved and most free’, which is an interesting description and immediately contrasts with the freedom espoused in Miller’s 300, where helots – or indeed, slaves of any description – are conspicuously absent.

The book starts out in ‘Lakonia, Greece’, where we are introduced to the helots, the subjugated population of Messenia. Text on the second page of the comic book proper explains that they are ‘beneath slaves’, who ‘bear the state’s fetters.’ Laconia itself is characterized as ‘a land where men are most enslaved and most free’, which is an interesting description and immediately contrasts with the freedom espoused in Miller’s 300, where helots – or indeed, slaves of any description – are conspicuously absent.

We are then introduced to the krypteia, which is actually less understood that the comic perhaps suggests, but commonly understood to be a kind of ‘secret police’ that terrorized the helot population to keep them subservient. We see what this interpretation of the krypteia gets up to: ‘The strongest are purged. The rest are cowed.’ In this way, the text dryly concludes, ‘utopia endures.’

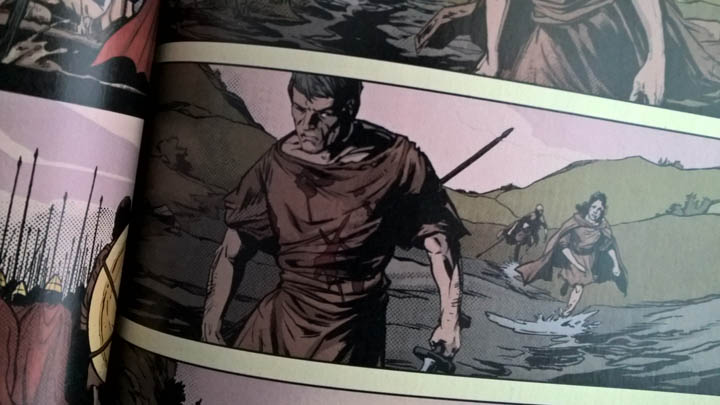

In the first two chapters, a group of Spartans, including an ephor, seek shelter in a helot house. One of the helots, Terpander, gets drunk and tells a story to insult the Spartans, after which a massacre ensues. One of the helots, Klaros, first runs off before coming back to aid his fellows. Together with a helot woman, Damar, they manage to kill all the Spartans save one Arimnestus, who flees. ‘What do we do?’ Damar asked. ‘We run,’ says Klaros. Together, they become the ‘Three’ from the title.

Back in Sparta, we are introduced to Cleomenes, one of the kings, and a Spartan named after the famous poet, Tyrtaios. The king must be Cleomenes II (r. 369–309 BC), and he refers to the Battle of Leuctra (371 BC) at one point (for more, check out Ancient Warfare IX.2); the blurb on the back of the book makes clear the story is set in 364 BC. The dialogue also makes clear that Cleomenes and this Tyrtaios were also physically involved with each other at one point, as if to increase the contrast with Miller’s 300 even further (where only the Athenians are referred to as ‘boy lovers’).

News now reaches Sparta about the helots who killed the ephor and his men and it is decided to send Cleomenes. One of the ephors remarks that, ‘If your father had not failed at Leuktra, we would not have this problem.’ Another adds that in that case, ‘Sparta, not Thebes, would hold dominion.’ There’s a brief flashback to Leuctra accompanied with the statement that the Spartans had ‘never lost such a battle before’, which is not entirely true, though an understandable thing to say in this context.

News now reaches Sparta about the helots who killed the ephor and his men and it is decided to send Cleomenes. One of the ephors remarks that, ‘If your father had not failed at Leuktra, we would not have this problem.’ Another adds that in that case, ‘Sparta, not Thebes, would hold dominion.’ There’s a brief flashback to Leuctra accompanied with the statement that the Spartans had ‘never lost such a battle before’, which is not entirely true, though an understandable thing to say in this context.

Cleomenes has no choice but to accept the task the ephors set him. He musters his bodyguard of 300 Spartiates to hunt down the three helots who killed Arimnestus’ father and their compatriots. With that, the stage is set for the rest of the book. There is lots of action, some good character moments, and the plot unfolds in a pleasing manner, with a bitter-sweet ending. I won’t reveal any particulars; you really should read the book for yourself.

There are lots of interesting details drawn from history. Arimnestus, for example, is branded a ‘trembler’ (a coward), because he ran away from the massacre at the start of the book instead of trying to kill the helots and defend his companions. His mother then wishes they had had two sons, ‘but that would have split the estates,’ a very real concern in antiquity. At one point, the fleeing helots come across a statue of Aphrodite who is equipped with a spear, and remark that ‘even the gods dress according to [Sparta’s] lunacy.’

The artwork is great, with a classic look to it reminiscent of older comic books. Archaeologically speaking, there isn’t much to complain about. The shapes of the shields in the book are off (they don’t feature the rims characteristic of Argive shields; they are shaped more like dinner plates). I don’t know of any extant examples of pins with lambdas on them, yet all of the Spartiates use them to fasten their red cloaks. A lot of the buildings also seem to be made entirely of stone, which was, by and large, not the case in ancient Greece – a helot’s house would almost certainly have featured mud-brick walls on stone foundations. One or two swords have blades with a funny shape and there are too many Corinthian helmets for my liking (this is the 360s BC, after all).

The artwork is great, with a classic look to it reminiscent of older comic books. Archaeologically speaking, there isn’t much to complain about. The shapes of the shields in the book are off (they don’t feature the rims characteristic of Argive shields; they are shaped more like dinner plates). I don’t know of any extant examples of pins with lambdas on them, yet all of the Spartiates use them to fasten their red cloaks. A lot of the buildings also seem to be made entirely of stone, which was, by and large, not the case in ancient Greece – a helot’s house would almost certainly have featured mud-brick walls on stone foundations. One or two swords have blades with a funny shape and there are too many Corinthian helmets for my liking (this is the 360s BC, after all).

The trade paperback version has a section with historical notes, followed by a conversation between writer Kieron Gillen and Stephen Hodkinson, a historian, specialized in ancient Sparta, and director of the Centre for Spartan and Peloponnesian studies, who read through the script and offered helpful notes. There’s a lot of interesting stuff in these pages if you’re looking for some of the reasoning that went behind the choices that the writer and artists made. Thoroughly recommended.

Update: D. Franklin tweeted us (@D_Libris) about an essay he wrote once for university in which the treatment of the krypteia in Frank Miller’s 300 is compared with Gillen’s use of that institution in Three. It’s worth a read.